Free from Discourse

On institutional accountability

On institutional accountability

With comments by James Gregory Atkinson, Nicholas Grafia und Geneviève Lassey

Accompanied by illustrations by Mona Chalabi

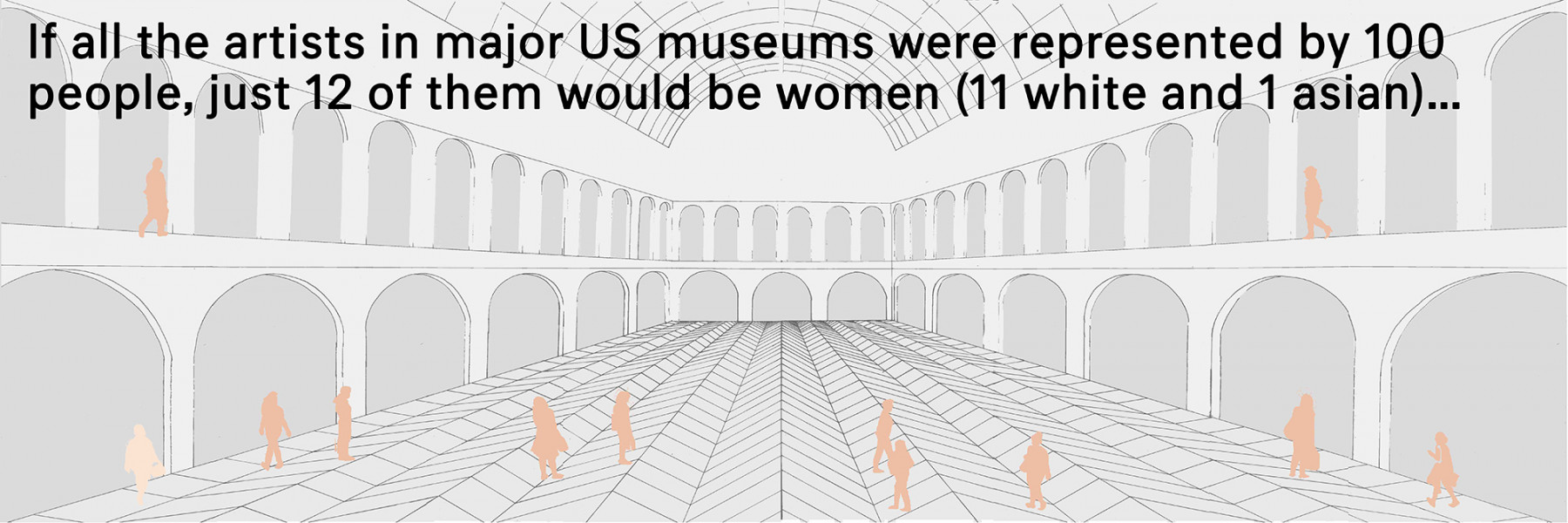

Women make up just 12% of major US art museum collections. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

“What is art allowed to do and where does its freedom end? As a society, this is a question we must ask ourselves again and again” is the beginning of the statement by the social media department of Frankfurt's Städel Museum, which reached various Instagram users via private message on 22 June 2020. The compact text was sent out in response to the numerous and critically connoted reposts concerning a painting by Georg Herold from 1981 – along with its accompanied label and with an emphasis on its title – that is currently on show at the Städel. [1] The painting, measuring 90 x 130 centimetres in landscape format, is quite large, but deliberately neither named nor depicted in this text.

The painting on hardboard is characterized by its expressive style and is almost entirely covered in a strong yellow, partly mixed with white, party applied in its primary tone. Yellow is also the dominating colour of the left background, where the head of the most prominent figure is placed. Parts of its head are yellow too while the rest of its body is painted in dark rose and violet. In any case, the body of the described male figure is clearly darker than the skin of its opponents that are shown in the lower-right edge of the picture. The facial expressions of the other figures are only vaguely visible in black contour lines in a complementary pastel green tone. Their gestures, however, are more decisive: one hand seems to grasp the figure on the left by the arm, another hand stretches far upwards. It is probably this hand that threw the brick that seems to fly towards the large figure in the middle of the picture. A traffic light separates the pack from the individual – whose distinguishing features unmistakably suggest a racist stereotype – and gives green light for the brick to be thrown.

The statement continues: “We as a museum see ourselves as a place of freedom, debate and contradiction. [...] We want to look with our visitors, not look away. We are sorry if the text accompanying the work is not clear enough in its anti-racist interpretation.” While one would not want to accuse the Städel of having any racist intention per se, one should take a firm and analytical look at the question of what is actually problematic about this work and the circumstances of its presentation; the debate certainly does not only concern the stereotypical depiction of a Black person, let alone the text accompanying the work. The problem lies deeper and must be grasped at its structural level. The criticism is less directed at Georg Herold as a person, even if one could certainly ask what the artist’s intention is in using this very motif. However, the artist’s intention is only of minor importance for the reception of the work. Neither does the critique of the picture imply to simply take it down – thereby even censoring it for the public. If this is might be the first acknowledgment of criticism, then this approach towards artworks is not a sufficient examination of racism in the long run. Instead, however, a discourse on the social implications, in which such an image can even be understood as an adequate response to current social movements, has to take place. Unfortunately, the Städel Museum does not seem to understand this. And this is why any commentary that legitimizes the Städel’s handling of this complex issue under the guise of artistic freedom fails to recognize the tragedy surrounding the lack of representation of BIPoC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) in public, German institutions and discourses.

For racism does not start with the killing of BIPoC in police hands and custody or when Nazis commit targeted attacks on migrant businesses in German cities. Racism also occurs when public institutions do not use their actual power to point out discrimination. The supposedly apolitical refusal to comment on social grievances is also an act of violence. With a slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement: “To be silent is to be taking the side of the oppressor!” Now, to hop on the bandwagon of political correctness when the ‘trend’ demands it is already a sign of opportunism. Not even trying to understand the debate, but rather making an unreflected statement like Herold’s image and refusing to criticize it, is sheer indifference towards the current socio-political struggles and the experiences of suffering BIPoC – not only in Germany but in our global society; no more than a white-saviour complex can be concluded from this behaviour.

It does not require an art education or specialist training in order to realize that the behavior of the Städel Museum follows typical patterns in debates about racism on several levels and that the museum has obviously not understood what anti-racist action and thinking truly means. It is about listening to people affected by racism and taking their concerns seriously. Instead, white men in positions of power – be it at the top of museums or in the editorial offices of leading media – insist that the image is not racist but anti-racist – without seeing the contradiction. [2] It is a typical case of whitesplaining: white people with institutional power and cultural capital – but without experience of racism – explain to non-whites from above and from their white perspective how racism works. Thus, racialized people are denied the right to determine for themselves whether they are racially attacked.

Men make up 88% of major US art museum collections. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

Referring to the intention of the artist is absolutely irrelevant: The depiction doesn't become less racist or hurtful. The same applies to the N-word used in the title of the painting. If one looks at the expression in its historical context, it quickly becomes clear what the intention of its original use was. It is also significant that those in charge at the Städel Museum don't even consider that a white artist – whether consciously or unconsciously – could incorporate his racist socialization into his art. The fact that it would be appropriate to finally give non-white artists space and a voice in the artistic debate on racism does not seem to have occurred to them. In this specific case, the fact that substitute policy is pursued at Städel is particularly evident in the fact that the voice is not given to those who need it more urgently than ever and are generally under-represented in this institution: instead of letting BIPoC speak up about their experiences of violence, it puts forward precisely the one position that the Städel certainly does not lack of. [3] Since the museum’s extremely extensive collection offers only limited diversity, it would also be a necessary step to internally oppose the prevailing ignorance and to reflect on why BIPoC artists and overall works of women are given nearly no space in the museum.

“Museums cement an art historical canon in their halls; not only is history displayed here, it is also actively replicated and produced. History is therefore also written in them. Writing this story entails ambivalent processes of ex- and inclusion, and the question always arises as to who exactly should tell, read or hear this story. You rarely reach everyone. With issues like racism and anti-racist efforts, however, this attempt should be clearly in the focus, because these affect and involve all of us in different ways and on a global level,” states the artist Nicholas Grafia, who is continuously dealing with institutional critique and racism in the art world on his Instagram channel.

However, it is not only the lack of inclusion of BIPoC artists but also the lack of visibility in leading positions in cultural institutions, in the roles of curators and cultural journalists etc. This is where a phenomenon emerges in the field of art and culture, which is inherent in the capitalist form of society and can be applied to almost all areas of work: gatekeeping. Even those industries in which BIPoC are increasingly employed – in particular, and especially in the light of the current crisis, employment of female BIPoC in underpaid jobs in the social sector can be cited here – the traces of the gatekeepers can be found and are going to maintain with the existing systems if it cannot be overcome structurally. The term, which is used primarily in sociology to describe a situation in which people in positions of power influence the educational and career paths, and thus the opportunities for achieving, of others, begins with the school system, in which mostly white teachers decide on the educational path of their pupils and it continues in their professional life. Although there may already be initiatives by individual institutions to generally ensure greater inclusiveness among employees by means of quotas, here too, only exceptions confirm the rule. And quotation should not be confused with real equality and equal opportunities.

If we go back to Herold’s painting and look at it without the accompanying text of the museum, we see nothing more than a lynching mob attacking the supposedly other. It is an outrageousness that is only surpassed by the insolence that the descriptive text does not take a clearly anti-racist stance at all but lingers in nebulous pictorial interpretations. The re-traumatisation that this must entail for BIPoC can be deduced from studies in recent years dealing with race-based traumatic stress. [4] The violence against BIPoC is so present and happens on a daily basis, there is no need to be taken up in such painting, especially if created by those who are not affected by this unfortunate experience of violence. In many cases, such images can even lead to post-traumatic stress disorders, so that the artistic reappraisal of these violent experiences should at least lie with the people affected. Otherwise, it is merely an instrumentalized aestheticization of this violence against BIPoC. On a different note, the historical context in which Herold created this painting should not be forgotten here as both the N-word and precisely this violence against BIPoC were still perfectly acceptable in 1981. Today, it is impossible to argue about a progressive provocation of the viewer through confrontation with the motif without being extremely thoughtless in regard to the violation of those who are still affected by racist violence today. For white viewers, it is hard to understand the effect this picture has on people affected by racism. Perhaps this is why most of the German newspaper articles and the text written by the Städel appeal to the presumed strength that it takes to endure such an image. They, the white viewers, are never confronted, either real or fictitious, with the gesture that extinguishes one’s very existence, which is so brutally expressed in Herold’s painting.

Moreover, there is no authentic understanding of art and society if only white artists continue to be exhibited and BIPoC artists are only asked to speak when their role as victims of racist violence is directly at stake; they are thus only subjected to an institutionally guided instrumentalization and are not respected with regard to the importance of their own oeuvre. The collection of the Städel, like many other art institutions, doesn’t include the work of BIPoC artists in its understanding of art history. However, a collection that strives to show modern and contemporary art, but only exhibits works by white, mostly male artists, does not give an authentic picture of the world. It only provides information from the standpoint of the white privilege and reproduces the perspective of the supposedly white supremacy. Again, it must be emphasized that the Städel is not an isolated case when it comes to institutionalized racism. The voices that rise up against this specific kind of supposed reappraisal do not sound here for the first time. One could mention, for instance, the debate about Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016), which was shown at the Whitney Biennial 2017 in New York and caused a far-reaching shit storm. [5] But the example does not have to be sought in the USA, because in Germany, too, one does not have to search long to find cases of appropriation and misguided debates. Most recently, for example, the collective Soup Du Jour set off a discussion in Berlin when it justifiably criticized Künstlerhaus Bethanien for not including a single Black artist in an exhibition on Afrofuturism. [6] Last year, many people in Frankfurt also experienced great displeasure and outcry over several exhibitions. The retrospective on Wilhelm Kuhnert at the Schirn Kunsthalle, King of the Animals, failed to address German colonial history and instead focused on an outdated romanticising image of the African continent, thus overshadowing a critical examination of the artworks and their history. [7]

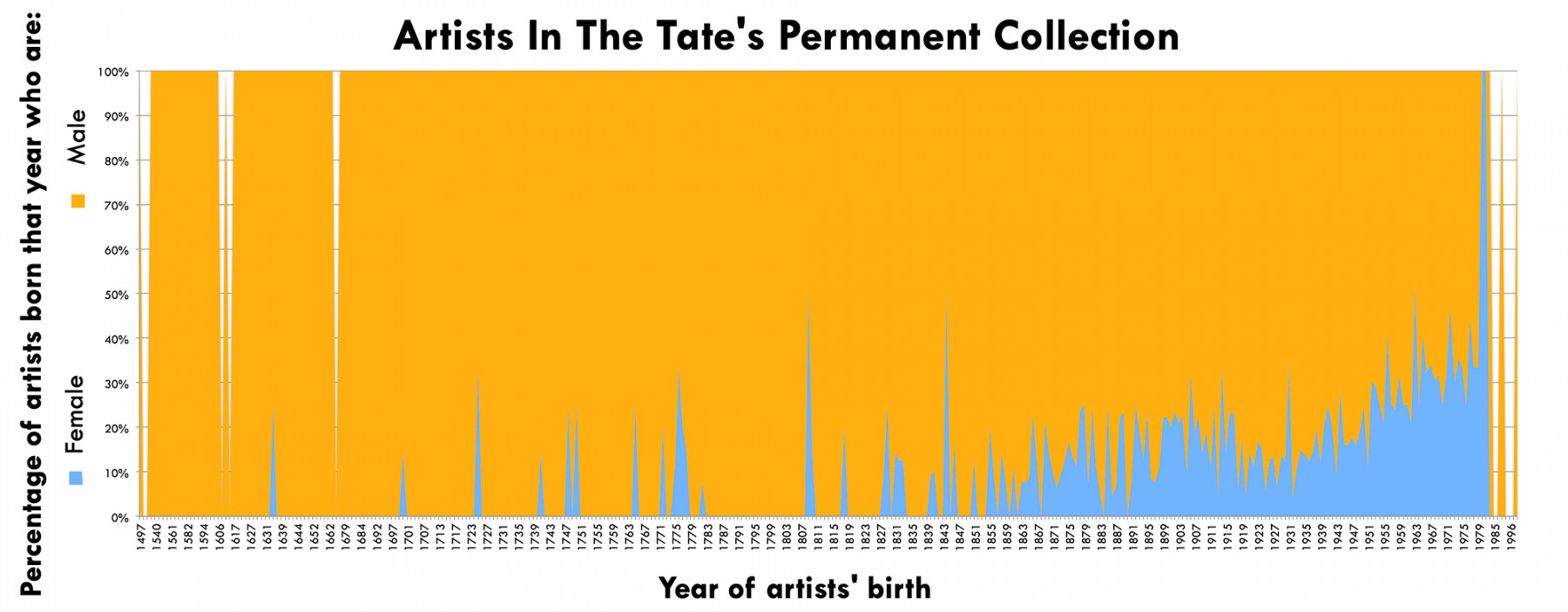

Many women and people of color are potentially absent from art museum collections. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

At the end of last year, the artist and curator James Gregory Atkinson, as well as the platform Contemporary And (C&) and other cultural workers criticized the Museum of Communication in Frankfurt on social media and the web for exhibiting a video work, which makes use of racist stereotypes in its depiction of Black people. [8] After the article Playing with Race appeared on Contemporary And, Atkinson commented on the blindness and lack of sensitivity of institutions and stated that they are "institutions that never really want to see our bodies and our history outside the context of art and media trends. Institutions that either tacitly accept racist representations or even promote them under the disguise of supposedly progressive art in the name of tolerance and artistic freedom. As a response when criticizing such depictions, we then hear again and again the same bland justifications of press departments that insist on freedom of opinion, artistic freedom, or speak of an age of change and the visualization of historical contexts. It often feels like an endless loop of institutional racism and cultural imperialism, criticism of the former, justification and apology. Unfortunately, little changes structurally. A loophole and a case of abuse of artistic freedom."

The criticism of a video work by Bruce Nauman in the MMK Collection should only be mentioned here in passing [9] - what is clear is self-explanatory. It would go too far to list and describe in detail all the examples of institutionalized racism in the cultural sector since they cannot be summarized in their entirety in a single text. Exactly this shows that the discourse must be understood as a continuous one that must be updated again and again. After all, the accusation of a single art space does not dissolve the deeply rooted social problem. The multitude of incidents nevertheless shows all the more clearly that this discourse does not need to look for a single scapegoat. Instead, we must look at the constitution of the German institutions as a whole. However, it is essential to give space to the individual case studies and their vehemence and to treat the debate not only in a structural and abstract way. Especially there the process of using and dismissing voices that critically comment on these inadequate expositions is most evident.

This also reveals the essence of the western art world. It seems that the inherent feature of contemporary cultural institutions is that the absolution of art can also be imputed to themselves. Understanding a museum as a "space for debate" here does not mean opening it up to the demands and suggestions of the visitors. The label rather portrays the museum as a neutral space in which this debate could be fought out - the museum itself is even apolitical, one might think. Like science, also seemingly apolitical and objective. However, if you go back only a few centuries, you can see that it was science that contributed significantly to defining and shaping the concept of "race". Museums are accomplices in this development. By exhibiting and repeating stereotyped imagery, they shape viewing habits over generations. Just take the example of Orientalism, which in the 18th century convinced numerous Europeans that the entire Middle East was a "land of plenty", but where all men were lazy and all women were courtesans. Remnants of this standardized way of seeing can also be found in today's debate about refugees when so-called Wutbürger (angry citizens) speak of economic migrants; and Indigenous people in North America are still associated with visual stereotypes from the colonial era.

In addition, by neutralizing one's own attitude, one evades any possibility of acknowledging one's guilt. Without facing up your own history and structure, there can be no real process of coming to terms with it. Then we are left with Instagram activism and a self-staging disguised as debate. But museums in Europe are mostly white institutions with a difficult colonial past. Many are severely reluctant to come to terms with their own history, although the colonial history of the origins of many museums - paired with the problematic purchase of works in the context of the National Socialism - demands a special responsibility. A responsibility that they cannot escape. But what is currently happening follows a classic colonial-paternalistic pattern: Whites decide over the heads of BIPoC for their own benefit. It's also interesting how Martin Engler, director of the Städel Museum's Contemporary Art Collection, argues the justification of the Herold painting, not realizing at all what an essentialist structural reversal takes place here in the perception of the work. According to Engler, the discourse should get by: "[...] without wanting to destroy the picture with the club or to take down everything that perhaps does not fit exactly into our society. [10] And this may be exactly the point at which the problematic aspect of the work has its roots and also in the context of which the presentation of the painting and the critical examination of it at least seemingly makes sense: it fits exactly into our society - because our society is racist. It systematically ignores and represses the voices of BIPoC. Instead of questioning one' s own position, one compulsively and defensively fishes for explanations. Perhaps the most cynical thing about Engler's statement is that he himself fits into society as a white man and decides that the criticism of racialized people is not part of it.

Furthermore, it would also be necessary to ask how the terms "society" and "social debate", as stated in the above-mentioned letter, are to be evaluated in the institution's understanding of these terms. Since the Städel Museum is a high-priced institution, the discourse space is only available to those who can afford to invest in admission. These restrictions on the visitors already reveal who leads the debate, but not who has a right to it and should make up a necessary part of the discourse - those who are exposed to social disadvantage and discrimination and on who's behalf privileged white people cannot speak on behalf of their socialization and educational background, or even replace their voices. Social and political participation is to be criticised precisely where such struggles are to be fought. Instead, and this is particularly evident at present, it is this closure of actual spaces that forces critics to shift to social media, but with striking force. As a public educational institution, however, the Städel has a social responsibility, just as it has the influence and prestige to help shape social discourses. If this duty is to be fulfilled, not only the question of representation but also the question of accessibility, of the availability and the right of disposal over works of art, must be posed; likewise, the question of the agency, under whose aspect would need to be negotiated how works by artists are institutionally appropriated, for in many cases their effect and meaning are partly already cut back by the curators and mostly even, free of context, no longer allow any debate about them.

A chart of all the artists in the Tate’s permanent collection. The upward-sloping blue line shows the emergence of women in the collection. Illustration: Mona Chalabi

Geneviève Lassey, sociologist, DJ, and author of the blog grossgeschrieben, also sees the problem at this interface of self-determination and representation: "According to the elitist orientation of many public cultural institutions, there is a lack of active artist positions, which is also a class issue. It is particularly evident here that showing and representing Black bodies is always accompanied by objectification of BIPoC. Where are my sisters, brothers and unrepresented minorities? With our artistic positions? Where are we? The current constitution of the museums and cultural scene as a whole is a symbolic expression of precisely those power structures of colonial continuities that have always been there. When it concerns art, the question of the power of definition should also be asked. Instead, one observes the instrumentalization of BIPoC artists, who are given space as objects or tokens but never as subjects. The active participation of BIPoC in the arts and culture must become more visible. At present, this visibility is limited to DIY projects, self-initiated actions such as demonstrations and the autonomous cultural scene, but without the support and participation of public cultural institutions."

It is long overdue to take experiences of racism seriously and now would be the time for curators, intellectual opinion-makers, cultural representatives, as well as for the feuilletons to reflect the disadvantages of BIPoC in their medium, profession and industry. This means to stop trying to shake off the blame for and repressing it for the sake of shame. The task requires understanding, self-reflection, and, above all, the ability to listen. It means to take seriously those voices that are yet too quiet to be heard. Perhaps this would lead to a productive contribution to this debate. If this discourse means a restriction of freedom for the Städel, it confuses 'freedom' with the institution's sovereignty of interpretation. In return, it should rather consider the repressions to which BIPoC have been exposed for centuries. The "tasteless brutal provocation" that the Städel attributes to Herold's work is something that BIPoC experience every day.

History cannot be undone. The conditions that made it difficult or even impossible for BIPoC artists to excel in the art world cannot be - in the historical sense - reversed. Nor can the cultural and artistic assets of colonized societies destroyed by Western imperialism be retrieved. However, apart from a look into the archives, it only needs a look back into the present, into the galleries and artists studios to find art there that belongs in museum collections. Works of art do not serve the satisfaction of aesthetic pleasure, they also shape our image of past and present world history. It is therefore not only the responsibility of each and every individual but decisively the role of state and municipal institutions, to proactively participate in the fight against these abuses and the reflexive redesign of art and cultural institutions. The Städel Museum should see the current discourse as an opportunity to seek dialogue, to accept criticism and to remove Herold's work. [11] Otherwise the museum will lose all credibility.

The original article 'Frei von Diskurs' was written in German and can be found here.

[1] The debate about the mentioned painting by Georg Herold started with this post on Instagram from 22 June, which was widely shared.

[2] Please see following articles published by German newspapers: Stefan Trinks, Was man aus bestem Willen erkennen will, 06.07.2020, FAZ; Michael Hierholzer, Malerei als Provokation, 30.06.2020, FAZ; Hans-Joachim Müller, Das N-Bild und der politisch korrekte Zeitgeist, 02.07.2020, WELT. In earlier versions of many of these articles, the writers had used the n-word and the complete title of Herold’s painting in their headlines. This was changed retroactively.

[3] This work by Georg Herold wasn’t exhibited in the Städel Museum until May this year when the collection presentation under the title ‘Back to the Future. New Perspectives, New Works – the Collection 1945 until Today’ opened.

[4] See Miriam Modalal's article for Response.

[5] For more information on this, we recommend reading Oliver Basciano's article for The Guardian.

[6] The debate was caused by this Facebook post by Soup du Jour, which criticizes the artist list of an exhibition on Afrofuturism at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, for which no BIPoC artists had been invited. For more information, please read Naom Rea’s article on artnet.

[7] In her article for Frankfurter Rundschau, the curator and author Mahret Kupka gives a thoughtful explanation about the problems of the exhibition and its lack of engagement with colonialism.

[8] Please read this article published on Contemporary And (C&). Additionaly, we would like to mention that an earlier website version of PASSE-AVANT (before October 2019) also featured on open letter which demanded the removal of Murray Gaylard’s work. Please contact the editorial office, if you have any further questions.

[9] The authors are referring to Flesh to White to Black to Flesh (1969), in which Nauman covers his body in dark paint.

[10] Cited from an interview with Hessenschau from 30.06.2020

[11] The following petition also demands the removal of Herold’s painting and can be signed here.