On Rosemary Mayer

by Rose Higham-Stainton

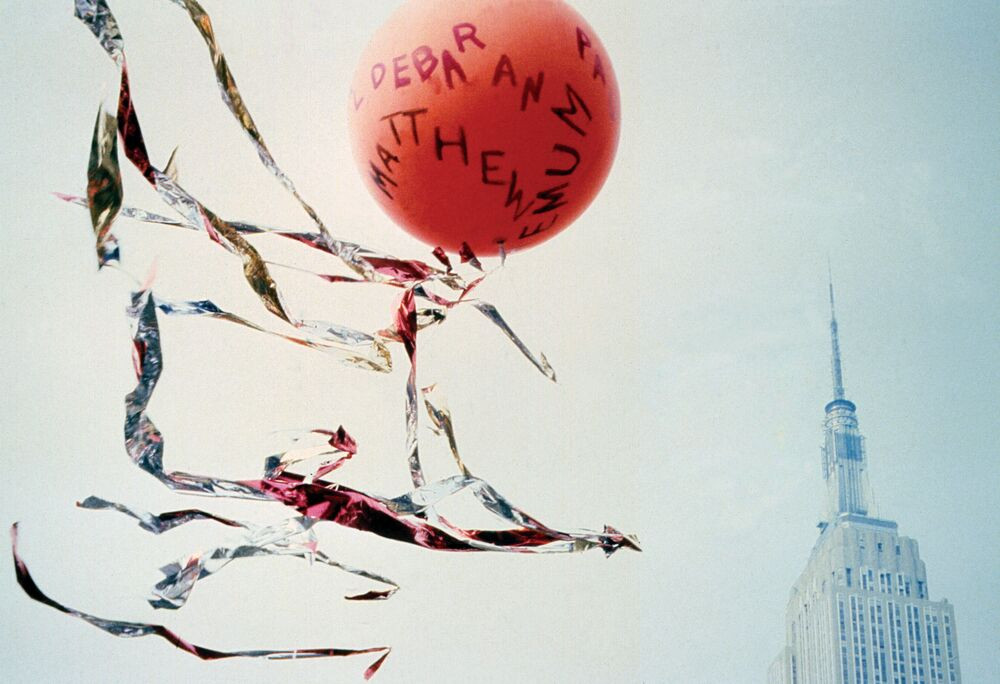

Rosemary Mayer, Photo documentation of: Balloon For A Birthday, 1978, installed on November 7, 1978, rooftop of 461 Park Avenue, New York, NY, © The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York, photogarphy: Rosemary Mayer

Barely visible, elusive and transparent, their motions caught in folds and layers of floating cloth. Angel sleeves, markers, records of their gestures, their presence.

- Rosemary Mayer, 1975

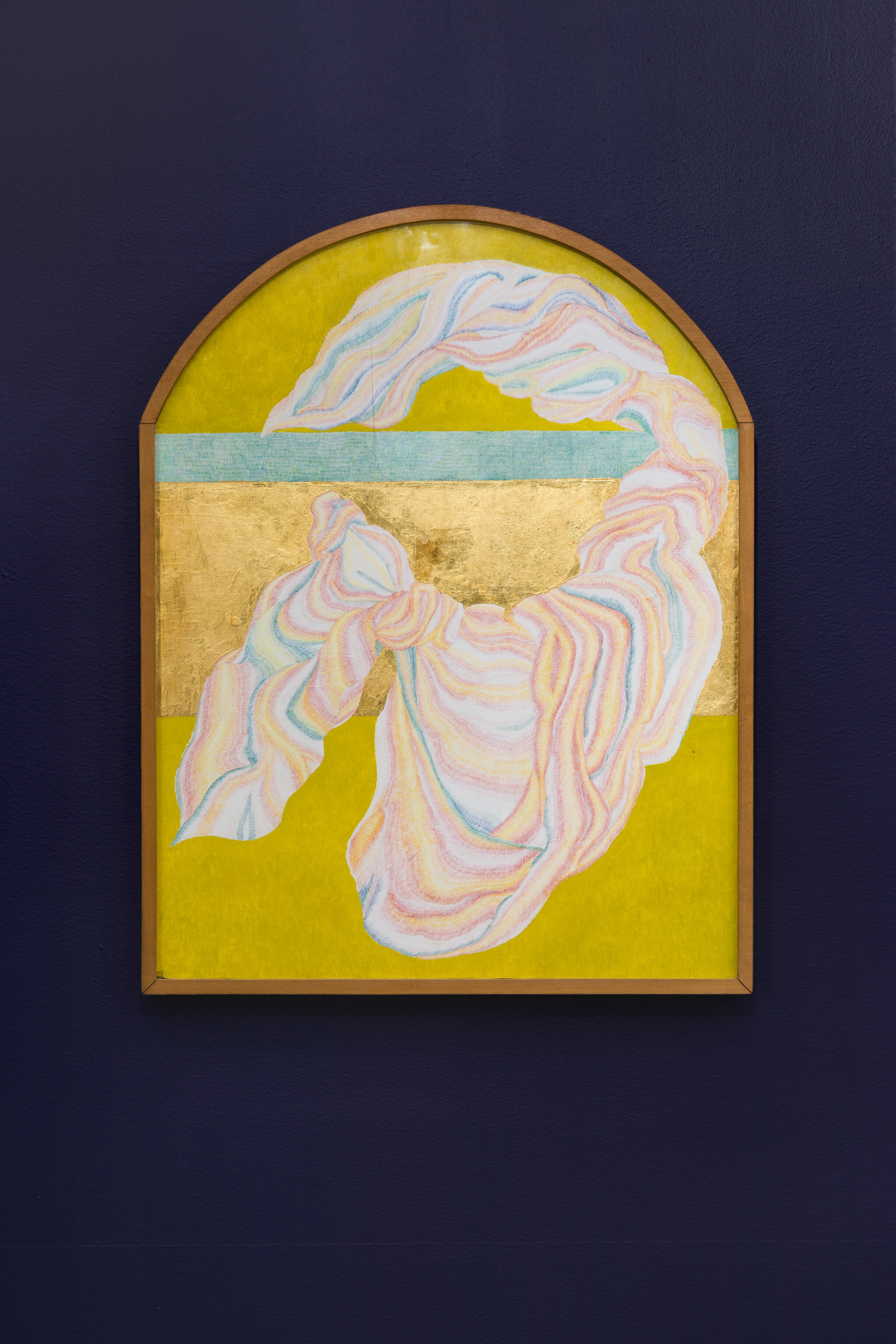

Mayer loved angels. They gave form to evanescence—its materials, gestures, bodies, lives. In Fifth Angel Sleeve (1973) Mayer redressed the Annunciation Angel from the Isenheim Altarpiece painted by Grünewald c. 1510, imagining the folds of fabric in a shock of saccharine colour crayon and oil paint, on a gold screen that arched like a reredos or an alter piece; the trailing fabric of the sleeve refers to a body in absentia. While in Hypsile (1973), tiers of iridescent mauve, burnt orange and boudoir pink are gathered like robes, but with no body inside.

There is no body in the work—there are never bodies, per-se, in Mayer’s work—but there are residues.

In Christian, Islamic and Judaic tradition, the angel, from the Greek angelos, from the Hebrew mal’akh (מַלְאָך) as in ‘messenger'—is a liminal being—a body that rises above time and place, winged like a bird, robed like a man. From the fallen rabbinic Azazel, to guardians Gabriel and Dubbiel, the angel is the intermediary between God and humanity—a connective tissue between life and death and thus liberated from a body in time.

Winged, blown and light, they rise and then they vanish.

Rosemary Mayer, Hypsipyle, 1973, Exhiibition view Ways of Attaching, Ludwig Forum Aachen, 2022. Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York. Photography: Mareike Tocha

For Mayer, the angel personified fleeting time in lightweight matter. In Galla Placidia (1973) fabric is stretched onto metal rods bowed in two elliptical parts like wings; Francesca Wade writes it is “distinctly human: a headless dignity with enormous sleeves, an apparition in the process of fading away.” [1] Apparitions, figments, residues—“the evanescence of everything is a notion that has always appealed to me,” Mayer said in an unpublished interview from 1978, “perhaps because I lost my parents when I was quite young.” [2]

Mayer was born into a Catholic family in Brooklyn in 1943. Her father was an upholsterer, her mother sewed, her uncle was a ribbon salesman and her sister Bernadette was a poet. Both their parents died when Mayer was 12 years old, which left a deep imprint on her life and work. In the mid to late sixties, she studied fine art first at the Brooklyn Museum School, and then at New York’s School of Visual Arts. Later she turned down a Ph.D fellowship for Harvard’s classic department to pursue a visual art practice. Mayer was briefly but formatively married to the poet Vito Acconci, after which she spent most of her life, until her death in 2014, in a Tribeca loft—living on a shoestring; keeping journals; throwing makeshift dinner parties, which she chronicled with her guests in huge ledgers; attending consciousness raising groups and in 1972, co-founding A.I.R Gallery —the first all-female cooperative art space in NYC. It was a living and breathing practice in which she made unfashionably decorative and ephemeral works amidst a climate of Richard Serra and Frank Stella, and for which she received little recognition.

Mayer’s process, materials, aesthetic and legacy were anachronistic—she was out of time.

Rosemary Mayer, The Fifth Angel Sleeve, 1973. Colored pencil, oil paint and gold on wood. Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Swiss Institute, New York. 2021. Courtesy of Gordon Robichaux, New York and ChertLüdde, Berlin and Peggy DeCoursey and The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York. Photography: Daniel Perez

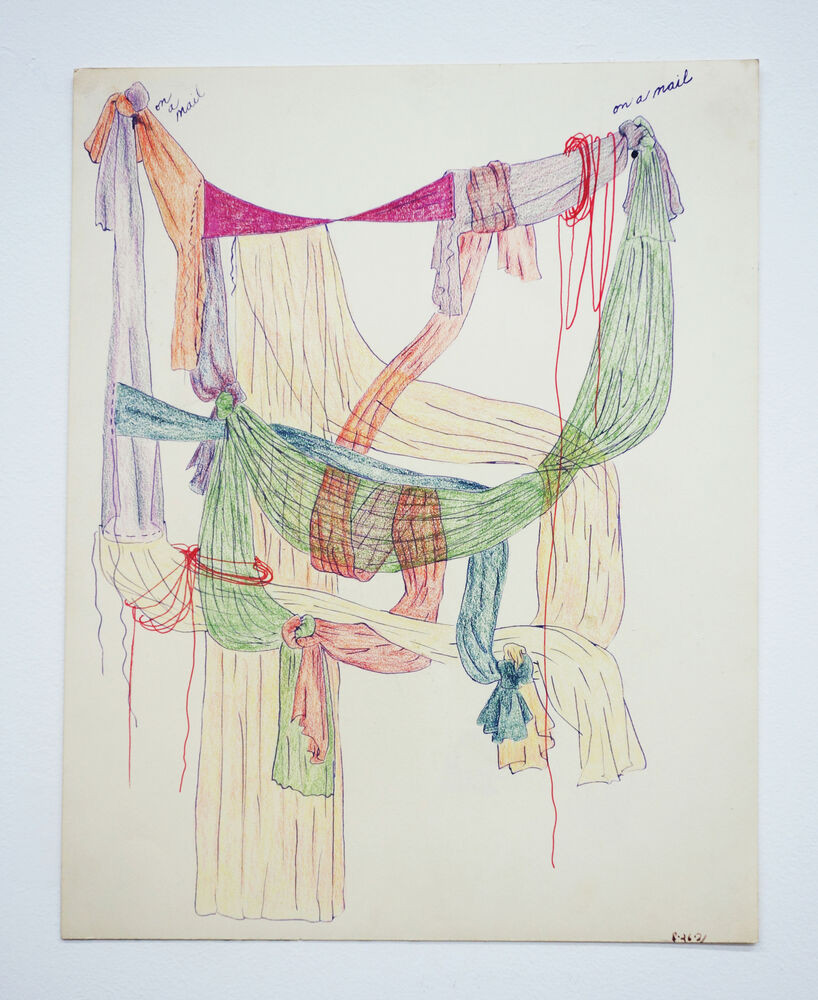

A series of painted fabric works titled Veils (1971)—their decorative protrusions splitting from their canvas—mark a formative moment for Mayer as she moved through and beyond the geometry of colour field painting towards the bristle and flex of fabric fibres. A few years later, she would immerse herself fully in lustrous cloth, hung on bowing frames. Limited to her small studio, she constructed the works from gauzy lingerie offcuts given to her by friend and poet Hannah Weiner who worked for a lingerie designer uptown and then documented and deconstructed them to make the space and materials for the next work. The pieces that she didn't dismantle, mostly perished in makeshift storage. A talented draftswoman, she made illustrative drawings of the clefts and folds of fabric, some of which operated as preparatory sketches for sculptures, while others were the works themselves. By the late seventies, Mayer began to enact the shifting and evanescent nature of her practice in durational works, or ‘temporary monuments,’ constructed from balloons and snow drifts, staging them in transient places like parks and farmers markets. For Some Days in April (1978) she commemorated her late parents and dear friend whose deaths and birthdays were in April by releasing decorated balloons over the farmers market in Jamaica, Queens. Rising up, the balloons marked a brink and delivered a message to civic onlookers.

And then, like the angel, the work vanished.

Nearly a decade has passed since her death—fifty years since early works like Veils—and we are just starting to notice her residue, largely thanks to an archive assembled by her niece and nephew Marie and Max Warsh and stored in their respective studios and living rooms in boxes, and under the bed. Her first institutional retrospective titled Ways of Attaching opened at the Swiss Institute in New York in 2021 and then to Ludwig Forum in Aachen, Germany in March of this year, before travelling on to Munich, and then later Bristol in the UK. The gallery spaces in Aachen recount the four decades of her work but the temporal and aesthetic transitions are subtle. One room is dedicated to a short yet crucial period in the early seventies, a fleeting moment, which appears today as fragile remnants. The ephemerality is emphasised by the faded majesty of Mayer’s cloth and the yellowing paper of her illustrations, presented under low lighting like gloaming—or theatre—in a futile bid to preserve that which was never meant to last.

Rosemary Mayer, Exhibition view, Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, Swiss Institute, New York. Courtesy of Gordon Robichaux, New York and ChertLüdde, Berlin and The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York. Photography: Daniel Perez

This encapsulates Mayer’s practice, through which she reconciled rather than dwelt on the past. She drew from rather than harked back, in works like Shekinah (1973-74) and Bat Kol (1974), which invoked feminine spirits derived from the Jewish tradition and the “invisible presence of deity.” Art Historian Dr Katie Geha writes that "“invisible presence” is an apt metaphor for Mayer’s oeuvre during this incredibly fertile period: a body of work centred on evanescence that, paradoxically, has a profound and lasting impact.” [3]

But what of the body—and the material of the body—in this body of work? Mayer’s “profound impact” is its fleeting matter—a too muchness of fabric without a body object. Or an abject body—non-affirmative. Because, “to be defined, it would seem, is to be fixed,” [4] Geha wrote and Mayer was famously wary of all definitions.

It is significant that the absent body in Mayer’s work is ‘feminine’—if not female. Resolutely non-figurative, these shrouded spaces reconcile the physical loss of her parents, with her female consciousness and a growing preoccupation with the body ‘object'—a political and personal struggle throughout her life.

Mayer grew up surrounded by cloth—her father’s upholstering fabric, her uncle’s ribbon stock, the cloth of the Catholic church—and absorbed it into her work as the primary medium and an “outgrowth of her painting practice.” She writes “I like fabric because it is sensuous—enveloping, how it hangs, graceful, beautiful… I like the materials I use too much—to subvert them into something where they aren’t important.” [5] Mayer attested to material over meaning, although they were often the same thing—illustrative drawings of cloth in Candy Crush colours were, unlike her preparatory drawings, only ever meant to be themselves—“last night I did some drawings of impossible knotted sewed & twisted pieces…finally something that makes sense to draw bec. it couldn’t exist any other way.” [6] The cloth was the point.

Rosemary Mayer, Untitled (08.26.71), 1971, colored pencil and colored marker on paper (35,3 x 27,9 cm).The Estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photography: The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York

But cloth—as cloth—weighs heavy with history and ideological meaning, compliant in slavery from cotton production to silk, and in the trappings of domesticity, mechanisms of care (and thus, also control) and notably here, gender—what it is to be a woman, what it is to operate in and outside its institution. In Galla Placidia (1973), fabric folds fluted like sleeves or layered like the weighty crinoline of skirts, are stretched on frames like whalebone corsets—faint semblance of that ideological meaning but “bigger in at least one direction than people,” [7] and excessive beyond reason. Chloe Wyma writes that Mayer’s work is “feminist and unapologetically ornamental” with its “sartorial and genital insinuations” [8], while obscuring the body from view.

Beyond autobiography and ideology, cloth is for Mayer a process of reconciling or redressing the body. Her fabric is always on the brink of unravelling—meaning and form. Sheer gauzy and iridescent fabrics appear as saccharine hues, secured with ribbons and ties in the trappings of textbook femininity; but up close definition fades—ribbons untether, colours flex (reds are murky like browns, purple dulcet to grey) or sit at odds with one another. While biomorphic wire screen and synthetic mesh sculptures like Crescentia (1975), with their protracting tubular limbs, imagine what a body might do if it unravelled.

Mayer revisions the ‘feminine’ as anti-monumental. Sensory and shifting, it loosens—shifts, splits, stirs. She makes light work of things—sheer fabric and funnels of air travel between the folds, making space where there should be none and speaking to an angel’s buoyant physiology. A surviving work titled Balancing from 1973, is formed of two triangular frames, constructed from a bowing rod and cord, suspended like pendulums from their tips, and preempts the weightier fabric sculptures of 1973 and 74. Silken mauve and pink cloth sweeps down and drapes loosely over the frames, with the motion of a skirt, discarded intimates, broken sails. Balancing feels personal and durational—like the aftermath of a body in the act—postcoital, even—and that what we see is the body’s residue.

Rosemary Mayer, Galla Placidia, 1973, Exhibition view, Ways of Attaching, Ludwig Forum Aachen, 2022. The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York and ChertLüdde, Berlin. Photography: Mareike Tocha

In 1976, the critic Lawrence Alloway wrote about Mayer’s work that “the feminine figure is absent as well as present, missing as well as given.” [9] Here Alloway refers not only to the notional body within Mayer’s work—and the dichotomy of absence and presence of women in society— but particular women lost to history. From the German canoness Hroswitha (1973), to Hypsile (1973)—queen of Lemnos, and Cassiopeia (1981) mother of Andromeda—Mayer (re)surfaces them in reams of material—a body simultaneously female and abject. Suspended on bowing frames, motioning like ship’s sails, and largely lost to time and inevitable deterioration—Mayer relieves these women of having a body fixed in the manner of portraiture, in the mastery of oil and a 5:4 aspect ratio.

In Adrian Piper’s obituary for her friend and fellow artist, she wrote that Mayer’s was a “body of work that was in love with the physical properties of materials, textures, clothes, and their exploration, but that easily cohabited with a serious and highly developed intellectual life.” [10] As a voracious reader of criticism, literature and the classics, fluent in Greek and Latin, Mayer was able to extract the stories of vanguard women—from ecstatic Teresa to the reformer nun Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz—, which she compiled in a series of intricate sketchbooks that revisioned their beauty in illustrative overlays.

For Mayer, time operated as a means of orientation and disorientation—she reconstituted Baroque majesty, the trappings of Catholicism, the drama of Mannerism to understand the present. On the brink of Baroque and with a propensity for colour, Mayer found affinity with the Mannerists and lovingly translated texts by the Italian painter Jacopo da Pontormo of whom she writes “I was living in Post-Minimalism, a time after a time of clarity, and Pontormo was in a time after the clarity of the Renaissance.” [11]

Beware of all definitions, said Mayer, seeking ambiguity—namely in the flex and illusion of the body in situ or absentia:

Once surfaces were clear, ordered and opaque, surfaces that quickly answer questions. Painting was flat. Sculpture had definite shapes with clean edges. Then forms dissolved, colors paled, began to float in uncertain atmospheres. [12]

Rosemary Mayer, Hroswitha, 1973, and The Catherines, 1973, Exhbition view Ways of Attaching, Ludwig Forum Aachen, 2022. The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York und ChertLüdde, Berlin. Photography: Mareike Tocha

Mayer’s work is as much about ways of detaching as it is about attaching—in a fleeting monument, a retributory breeze, a snowmelt. I do not mythologise the work’s temporary nature—it was often the price of self-criticism, constraints of space and money or time’s inevitable deterioration. So that the work, already lost on the art world, period—has largely been lost to the world. There is nothing to grip onto.

But detachment can open things up. The finite fibres of fabric, its bristle and flex and inevitable ware, became for Mayer an opportunity—a material resistance against infinity and against monuments. In 1978, she wrote “the art object should not be still, unmoving and independent of its circumstances. Nothing is.” [13]

Nothing is, says: the absent body. Mayer’s fleeting matter rises in the ether—outdoors in parks and farmers markets and in cloth like sails—creating distance between her and the (art) world. To this day, Mayer inhabits a space beyond her circumstance, beyond time, beyond even a body and thus beyond the power structures that hold us — the institution of the body, the body under patriarchy and the violence done to that body. In her journal from 1971, she talks often and openly about being broke, failing to earn money from her art and wanting to be thinner. That final admittance appears at odds with her love of food and throwing dinner parties and her luscious fabrics but articulates a desire for agency—to extract her body from, rather than be omitted from, the picture. Works like Hypsile with its empty hooped frame tiered like frosting, express Mayer’s contradiction—her appetite and a body in absentia; she leaves us with the residues. In Recollections of My Non-Existence, Rebecca Solnit writes, “We were trained to make ourselves desirable in ways that made us reject ourselves and our desires. So I fled.” [14]

Mayer too, renounces the body, figuratively.

Of her work, Geha asks "how do we preserve a work that no longer exists?” But preservation says monumentalism, and Mayer refused to stand still, knowing that the body depletes under the weight of time and so too does the cloth we shroud ourselves in. “Capturing the evanescent,” [15] Mayer moves beyond monotheism, beyond a godhead, beyond, even, a body—the weft of a sleeve, caught in the act of disappearing.

Rosemary Mayer, Exhibition view Ways of Attaching, Ludwig Forum Aachen, 2022. The Estate of Rosemary Mayer, New York. Photography: Mareike Toch

Rosemary Mayer - Ways of Attaching

05/03 - 22/05/2022

Ludwig Forum for International Art

Jülicher Str. 97-109

52070, Aachen

[1] Francesca Wade, "Rosemary Mayer at the Swiss Institute", London Review of Books: https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v44/n01/francesca-wade/at-the-swiss-institute

[2] Rosemary Mayer, "Changing Time: An Introduction" by Dr Katie Geha, Beware of All Definitions: Selected Works 1966-73 edited by Katie Geha and Marie Warsh (2017, Lamar Dodd School of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, GA) p.6.

[3] Rosemary Mayer, "Changing Time: An Introduction" by Dr Katie Geha, Beware of All Definitions: Selected Works 1966-73 edited by Katie Geha and Marie Warsh (2017, Lamar Dodd School of Art, University of Georgia, Athens, GA) p.8.

[4] Ibid, p.2.

[5] Ibid, p.5.

[6] Rosemary Mayer, Excerpts from the 1971 Journal of Rosemary Mayer, (2020, Soberscove Press, Chicago), p.119.

[7] Rosemary Mayer, unpublished interview 1974, from Geha p8. are

[8] Chloe Wyma, Rosemary Mayer: SOUTHFIRST, Artforum, 2016 ( https://www.artforum.com/picks/rosemary-mayer-64534).

[9] Lawrence Alloway, Artforum, 1976, https://www.swissinstitute.net/exhibition/rosemary-mayer-ways-of-attaching/

[10] Adrian Piper, ‘Rosemary Mayer’, Artforum, 11 December 2014.

[11] Marie Warsh and Gillian Sneed, "Diaries of an Artist: The Art and Writing of Rosemary Mayer", The Brooklyn Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2016/04/criticspage/art-and-writing-of-rosemary-mayer

[12] Ibid.

[13] Rosemary Mayer, “Passing Thoughts” (unpublished artist"s statement, November 4, 1978, Rosemary Mayer Archive).

[14] Rebecca Solnit, Recollections of my Non-Existence, (Granta, London, 2019), p.81.

[15] Marie Warsh and Gillian Sneed, "Diaries of an Artist: The Art and Writing of Rosemary Mayer", The Brooklyn Rail: https://brooklynrail.org/2016/04/criticspage/art-and-writing-of-rosemary-mayer