On Howardena Pindell

Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, UK

by Rose Higham-Stainton

"I want to caveat this text on Howardena Pindell by saying that it was tentatively written for another publication who decided they found 'the artist intriguing but somehow a bit too off the beaten track'' and decided not to run the piece. This response alludes to exactly the kind of social and racial discrimination that Pindell, now seventy-nine, attempted to broach in her career as a curator and continues to do in her work as an artist." Rose Higham-Stainton

----

Can a day be circular—not just its time but the things within it? Most of us end where we begin, homing in or back. While Howardena Pindell punctured the circularity of the day by bringing art-making into the office and her office into the work. For over fifty years, she has employed circularity as a pressing and political tool for discussing labour, race, gender and art-making.

Pindell first impressed the circle with a file-punch (what the British call a hole-punch), scoured from the office at MoMA where she was Exhibitions Assistant in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books. The ‘blending of office and studio work’ was not for comfort, but from a need to rethink the parameters of administrative worker and art practitioner. Like Adrian Piper’s book-keeping and Rosemarie Castor’s Pitman shorthand, interpolating the materials and gestures of administration into art was a commentary on the institutional barriers faced by woman and people of colour—lower pay and lowly positions—trying to make work and a living.

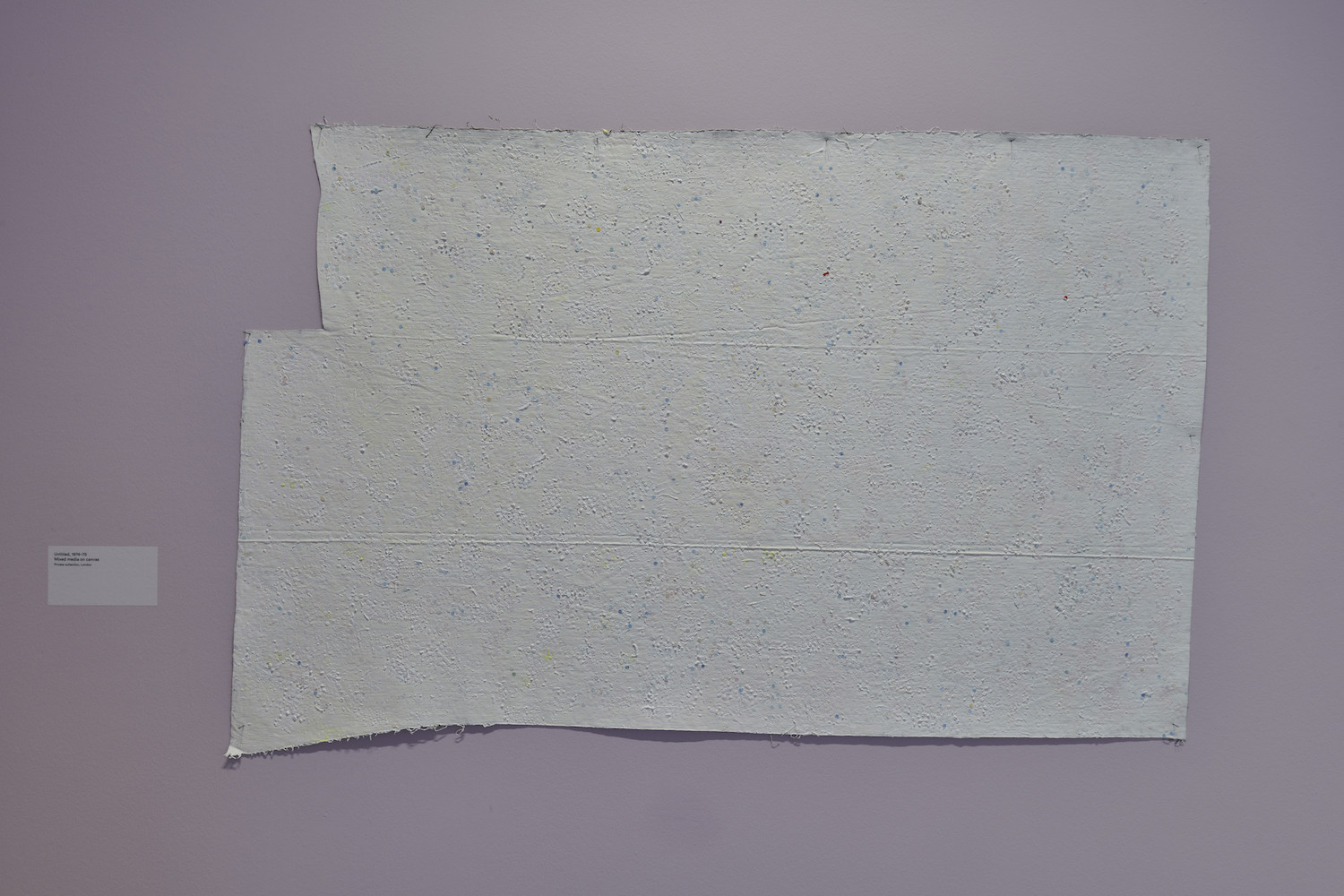

Howardena Pindell, Untitled, 1974-5. Installation view, "Howardena Pindell: A New Language", Kettle’s Yard, 2022. Photography Jo Underhill.

Demanding in its gesture, the file punch’s elliptical openings formed a stencil for her paintings, which Pindell fabricated from a series of manila folders glued together, and the punch’s flighty debris or paper chads were affixed in their hundreds onto canvases encrusted with glitter, face powder, glue. ‘Howardena Pindell: A New Language’ at Kettle’s Yard, is the artist’s first institutional exhibition in the UK and focuses on the sugary abundance and patternation of these ‘shaped abstract canvases’ alongside Pindell’s explicitly political and graphic ‘memorial works’ that name and enumerate those who have died from institutionalised racism, sometimes on stitched canvases fixed in daubs of thick paint.

The circle — a form produced by paper chads, oil sticks or cray-pas and through a process of repetition — guides our movement around the galleries and between these two crucial stages in Pindell’s oeuvre as an ambivalent and benevolent presence. From the large painted black canvas of Diallo (2000) bearing the names of two un-armed black men, Amadou Diallo and Patrick Dorismond, killed at the hands of police and peppered with guns and chads like shrapnel, to the Azul shimmer of canvases like Plankton Lace #1 (2020) and pencil drawings, and chad collages in which Pindell places hundreds of paper chads in rows, upending numeration in ‘nonsense numbers’ the circle elicits the holes within old systems and demands our need for a whole new language. Pindell traces her obsession with it retrospectively, back to an early childhood memory she has of stopping for root beer with her father in one of the southern states of North America / US. After quenching her thirst, she noticed a little red circle at the bottom of the glass, which was once used to distinguish utensils for Black people from those for White people in the South and so became a conduit for segregation. This initiated a lifelong obsession with the circle as a way of marking the scale of trauma—the relentless micro and macro aggressions that make it. And what could be more political than a circle—a thing that pre-dates history.

Howardena Pindell. Installation view, "Howardena Pindell: A New Language", Kettle’s Yard, 2022. Photography Jo Underhill.

Howardena Pindell was born in Philadelphia in 1943. After studying art at Boston and Yale Universities, she took the job as Exhibitions Assistant at MoMA and later as Associate Curator, serving on the Byers Committee investigating racial exclusion in museum acquisitions and exhibitions. In her own practice, she was starting to stray from the figurative and representative modes she’d learnt at Yale. By the late sixties and early seventies, she was gaining recognition for her canvas grids, circles and repetition, encouraged by the Serial Art movement. But this same commitment to abstraction saw Pindell’s work mooted as ‘non-political’ by both the Black Arts Movement and the white establishment—she was not, they said, depicting the African-American experience. In 1972, she co-founded A.I.R (Artists in Residence)—the first women’s cooperative gallery in New York, which was divisive if not complicit in racial divisions. The gallery corroborated Pindell’s un-placeability within the art world. This was, in part, a conscious decision: “I am an artist. I am not a so-called ‘minority”, she once said, “‘new’ or ‘emerging’ or ‘a new audience’. These are all terms used to demean, limit and make people of colour appear powerless.”

Under the tempered daylight of Kettle’s Yard, these works appear at odds with one another—the more decorative works following those that explicitly lament the victims of racism intend aftercare and healing. It is an important discomfort that also marks the periods prior to and following a car accident in 1979 in which Pindell suffered short-term memory loss and used art-making to retrieve or circle back into the past. But she does not submit to linear chronology and moves back and forth between these impressionistic moments evident in the glittering veneer of Plankton made as late as 2020.

Howardena Pindell, Tarot: Hanged Man, 1981. Detail. Photography Jo Underhill.

The circle endures, marking the many spaces through which Pindell has roamed—curatorial office, committee board and latterly classroom, as professor at the State University of New York, in Stoney Brook—while also keeping count of the victims of oppression at the intersection of gender and race. For Pindell, abstraction met activism in the “collation, tabulation and distribution of data” writes Anna Lovatt from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, in the exhibition catalogue titled Howardena Pindell A New Language—sometimes she is counting lives, other times it is repetition itself that elicits the violent and unbreakable systems that hold people down, evinced in the tireless and enduring mark-making of 1-6031 with Additions, Corrections and Coffee Stain (1973). Elsewhere, in Parabia Test (1974), Pindell precisely and laboriously placed chads inscribed with letters from the Phoenician alphabet between graph paper and vellum using tweezers. By holding ancient marks between a sheer surface for technical drawing, and an old opaque one, she paid heed to a theory circulating in the late sixties that it was in fact the Phoenicians in the seventh century BCE, not Christopher Columbus, who first connected the ‘Old World’ with the Americas. In Parabia Test, rather than reacting to the social fracture of her immediate surroundings, Pindell traced it back through the ‘fractured epistemologies and global histories’ that had enslaved nations.

Howardena Pindell, Rope/Fire/Water, 2020. Digital video, colour, sound, 16 minutes Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery and Victoria Miro.

Moving image, by its very nature, makes incremental changes on average 24 times a second. In the video work Rope/Fire/Water (2020), which Pindell ideated in 1980 but did not get the support to make until 2020, pixels amass into archival images of lynchings before splintering into darkness and the metronome, like a death toll against a black screen. Nineteen gruelling minutes of archival footage, data and stats, document a long history of racial attacks in the United States—first lynching and later race crimes connected to the civil rights movement, cycling through a relentless stream of violence produced again and again that stings like the metal of tweezers and nails from Pindell’s immaculate process. While in the seminal work Free, White and 21 (1980), Pindell appears to shed skin, peeling latex from her face, as she performs a conversation between herself as a young artist and a white feminist who disputes and later dismisses Pindell’s claims of racial violence among the feminist movement. The cruelty of the white woman in Free, White and 21 appears in utter contrast to Pindell’s care for, and consideration of, the viewer in this exhibition, with its unmissable trigger warnings and healing works that draw painful viewing experiences to a close. From within these explicit works, Pindell grapples with the incalculability of death and encircles us in a lament.

Howardena Pindell, Free, White and 21, 1980 U-matic, colour and sound, 12 minutes, 15 seconds, Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery and Victoria Miro.

‘Howardena Pindell: A New Language’

Howardena Pindell

02/07 – 30/10/2022

Kettle’s Yard

Castle St, Cambridge

CB3 0AQ, UK