Angharad Williams

Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf

by Gabriela Acha

"After this sort of thing," asks the car-crash survivor Dr Helen Remington, "How do people manage to look at a car, let alone drive one?"

– Zadie Smith on J.G. Ballard's novel Crash

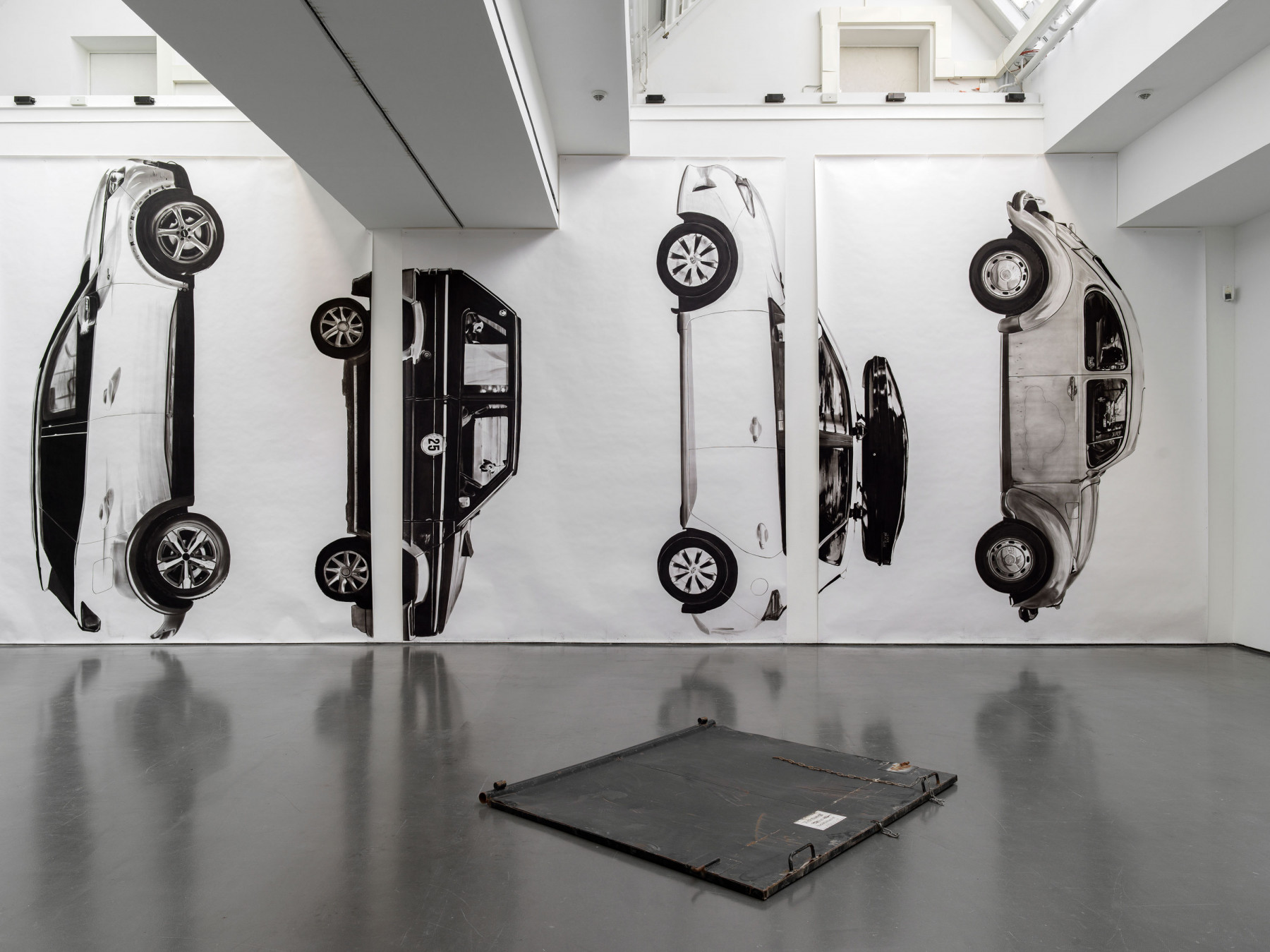

Angharad Williams, What it feels like to live another day, 2022, detail, Cars, 2022, installation view "Eraser", Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022. Photo: Cedric Mussano

In her 2014 article Sex and Wheels for the Guardian, Zadie Smith revisits at J.G. Ballard's novel Crash. Following on the writer's perception of his work as the “first pornographic novel about technology”, Smith reflects on Ludwig Wittgenstein's statement that language is better understood through its use, and not through its absolute meaning. She rises the question of whether pornography isn't ultimately “the purest example of humans 'asking for the use'.” In Crash, the protagonists race and crash their automobiles, using its dramatic momentum to get laid, perform sexual intercourse, and feel more alive. The exchange between organic and mechanical bodies, and their fluids, blur “the distinction between humans and objects [which becomes] too small to be meaningful.” Everything and everybody, becomes thus a thing and uses each other; cars become flesh and humans become machines. In Smith's words, “things are using things” in this dystopian tale. [1]

Cars challenge time and space by conveying passengers from one place to the other at ‘unnatural’ speeds. Like boxes, they have the potential to protect from catastrophes, but also to lead to them. As Ballard puts it, they are the death-drive “Thanatos”, and driving is death itself. On one hand, automobiles remain a symbol of progress, as they have led to the development of certain infrastructures in order to speed up the commutes, or transport goods. Roads and highways shift landscapes and interfere with the (sometimes ancestral) habits of the ecosystems' inhabitants. These developments have, thus, embodied political agendas and condition many human and non-human beings and the ways of living that are permitted in a space, often leading to drastic environmental consequences. On the other hand, automobiles also symbolise class positions and economic means. Cars express the psychologies of consumers, which materialises in the choices they make and the products they use. If a future civilisation would extract a selection of current consumer items in ensuing centuries, I wonder what kind of behaviour and social dynamics they would infer about us.

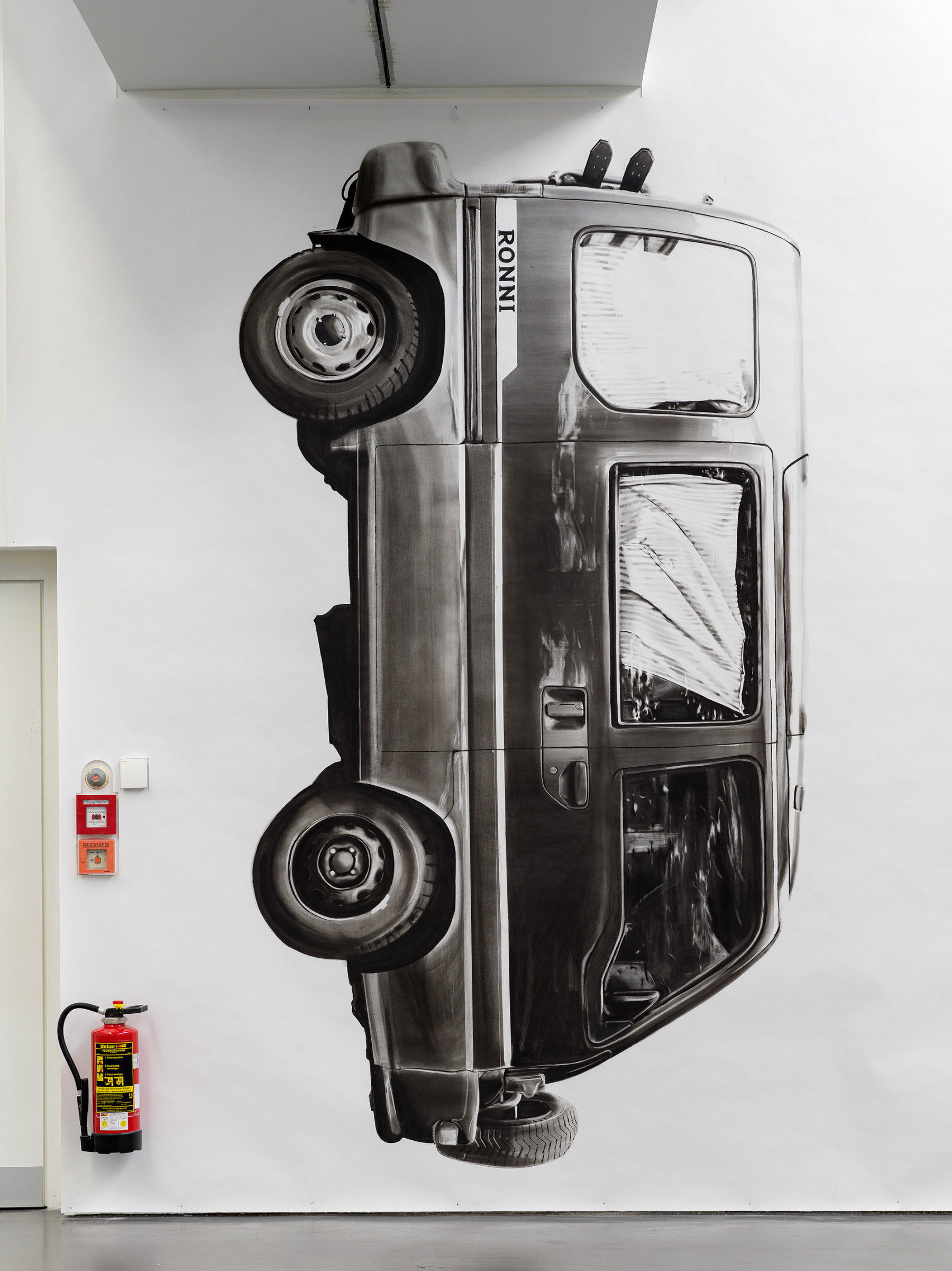

Angharad Williams, Cars, 2022, detail, installation view "Eraser", Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022. Photo: Cedric Mussano

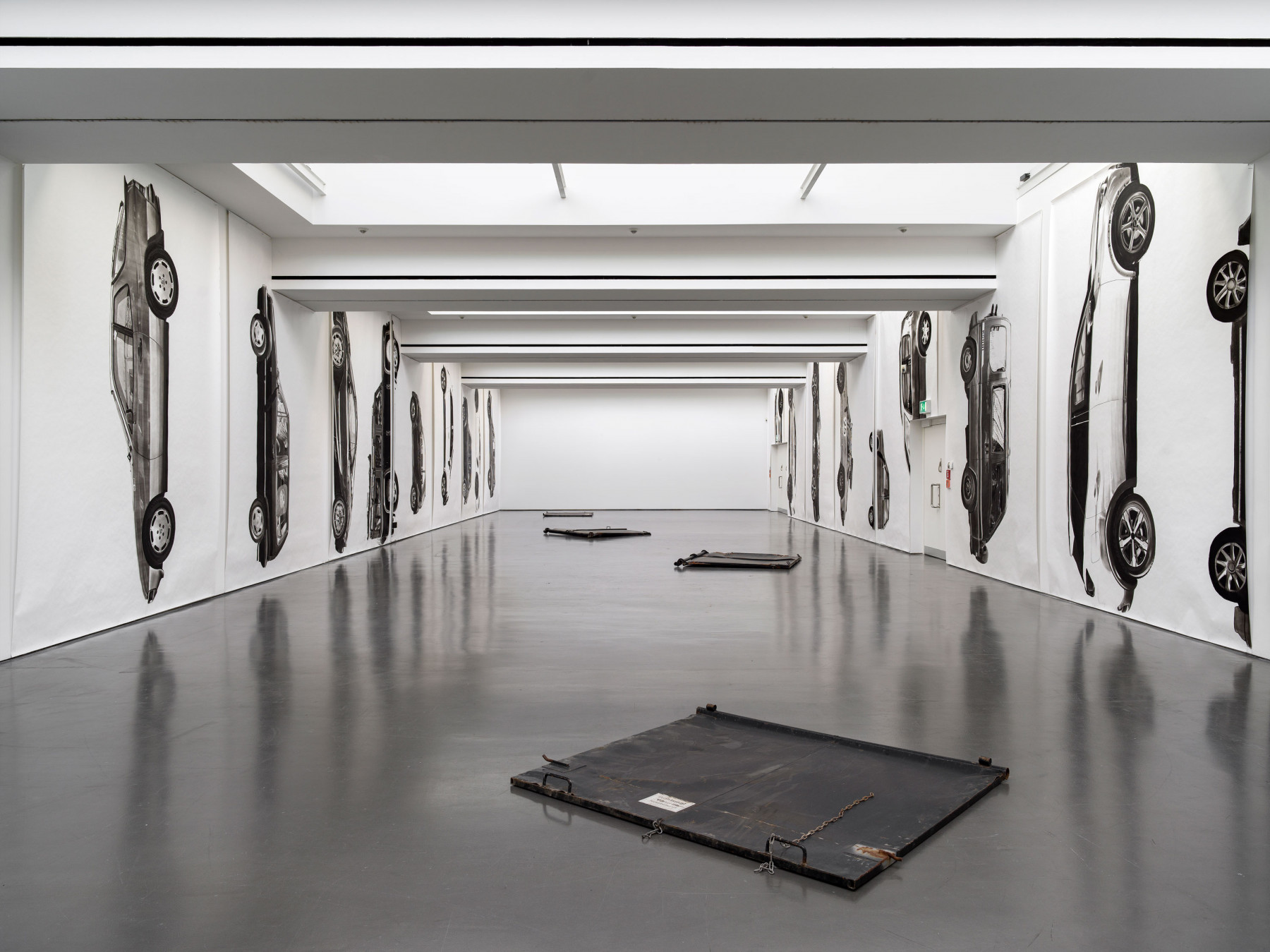

In Angharad William's exhibition „Eraser” at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, the artist portrays a series of automobiles in real scale, floating vertically on a white background (Cars, 2022). The sleek monochromatic, rigorously detailed figures surround a series of found container lids lying on the ground (What it feels like to live another day, 2022). At first, it seems that Williams's charcoal drawings oppose Smith's idea of the “pornographic”, avoiding a literal depiction of their “use” and exploiting their aesthetic essence and meaning. As in a museum vitrine, extracted from their context in an anthropological, even fetishistic register, these familiar objects can be analysed as single entities. However, if one devotes attention, the imagery is also prone to trigger a number of possible associations, turning the cars into testimonies of a whole interconnected, expanding framework of eras, means, and technological and aesthetic trends.

The manual illustrations show a plenitude of details, in a similar fashion to the 17th century depiction of Giulio Cesare Casserius, made in a time when skilled hands were trusted as conveyors of scientific objectivity. Since technological devices can depict nearly anything at a macro or micro level, here, manual drawing is relegated to the realm of subjective self-expression. Furthermore, the increasing popularity of AI engines such as DALL-E or GPT-3 as artistic tools, supplementing familiar labour outsourcing including industrialised production of art works (or indeed the time-honoured ‘studio system), one may question whether art makers have become little more than prompt generators, and what the role the artist actually plays in production these days. Perhaps in response to that, „Eraser“ is an ode to the manual labour and imperfect, decelerated execution in artistic expression.

Angharad Williams, Cars, 2022, detail, installation view "Eraser", Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Williams' “machinic” bodies are exhibited in a meticulous seriality, looking uniform, like a procession of religious icons. At the beginning of the 20th century, the Futurists already “wrestled with the icon of the motorcar”, and expressed in their 1909 manifesto, that the “modernist desire [is] to replace our ancient gods and myths with the sleek lines and violent lessons of the automobile.” [2] In their devotional elevation of technological objects as icons, their ideas of destruction and reconstruction, the embrace of deliberate chaos, and longing for a new order, these sentiments do not feel particularly distant from our current time and circumstances.

Not only are the differences between human and non-human agents sometimes blurred – as Smith claims – but also the differences between reality and fiction. The violence and extremes depicted in fictional narratives are often overtaken by real events, undermining any feeling of stability, an intrinsically modern position. Ballard's own experience of war and exile made him perceive reality as a kind of “stage set”, where nothing could be taken for granted, as it “could be dismantled overnight”. [3] His depictions of explicit violence are just a reflection of what is already in front of us, and which is permanently conveyed through different media, more so now than in even Ballard’s time. Yet, instead of familiarising us with the imminence of death, the constant exposure to violence and death feeds an “irrational fear”, an “intense paranoia and a constant obsession with safety. [ … ]”. [4] This compulsion necessitates the building of higher fences and more security devices, which keep society segregated and surveilled.

Angharad Williams, Cars, 2022, detail, installation view "Eraser", Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Williams gestures towards the vigilant gaze of rear mirrors and tactical security gear by subtly implementing distorted reflections on the shiny surface of her drawn automobiles. These visions recall the convex mirrors placed in shop corners in order to prevent shoplifting – in the absence of a camera system – as well as indirect portraiture in the tradition of Flemish painting, for example in Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait. In „Eraser“, there is one portrait, that of the artist's friend Enver, whose leisure time in the park is documented in real time in the 7 minute video clip entitled Enver’s World (2022). Enver’s World is shown in a different room from the main hall. Thus the particular is sorted from the general in Williams exhibition, tracing a relationship between the human from the non-human, as well as notions of inside and outside.

Back in the main hall, a set of found container lids is placed on the ground, as though leading to a cellar, or perhaps a mine, or somewhere in the mythical underworld. But these lids cannot be opened; nor do they lead anywhere else. Nevertheless, their presence creates the illusion of being kept outside of somewhere. In „Eraser”, Williams recurrently points to hidden details the viewer might want to see, but which cannot be seen. Navigating the space conveys the realisation that some bits of information remain attainable only in a subtle and indirect way, revealed only in fractions and through hints. The only fully attainable sense is the feeling of being kept beyond the sanctum concealed by these doors. Although the objects proposed by William are technically abstracted and devoid of context, they definitely beckon the viewer to engage with them, but in a rather sensual, flirtatious, and furtive way.

[1] Zadie Smith, Sex and Wheels: Zadie Smith on JG Ballard's Crash, The Guardian, 2014 https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jul/04/zadie-smith-jg-ballard-crash

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

Angharad Williams, What it feels like to live another day, 2022, Cars, 2022, installation view "Eraser", Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 2022. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Eraser

Angharad Williams

02/09 – 27/11/2022

Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen

Grabbeplatz 4

40213 Düsseldorf