Nikita Kadan at 91 Galerie in Frankfurt

by Alica Sänger

The exhibition and artistic research project “Flooding” traces the multi-layered topography of memory in the city of Stanyslaviv, today’s Ivano-Frankivsk in Ukraine. Navigating through its re-entrants and crevices, artist Nikita Kadan and co-curator Alona Karavai interrogate established narratives surrounding the remembrance of the Holocaust in the city, focusing in particular on the events of what would historically be remembered as “Bloody Sunday”. Through the years, what transpired on that day shaped the cityscape, while historical specificities were obscured and remained submerged at the bottom of the municipal lake. “Flooding” not only exemplifies the fluidity and resilience intrinsic to our collective memory but also highlights its susceptibility to distortion, questioning notions of collective trauma, mourning, and complicity.

The newly opened 91 Galerie in Frankfurt am Main, an art space dedicated to contemporary art from Ukraine, presents the second iteration of the exhibition which was originally shown at Asortymentna Kimnata in Ivano-Frankivsk in early 2023. The groundwork began in 2020, when Kadan was researching the city’s history. Next to the artworks, various printed texts are installed on a pillar in the center of the space, including reports from contemporary witnesses and contributions from researchers that offer an insight into this process and provide the historical background of the exhibition.

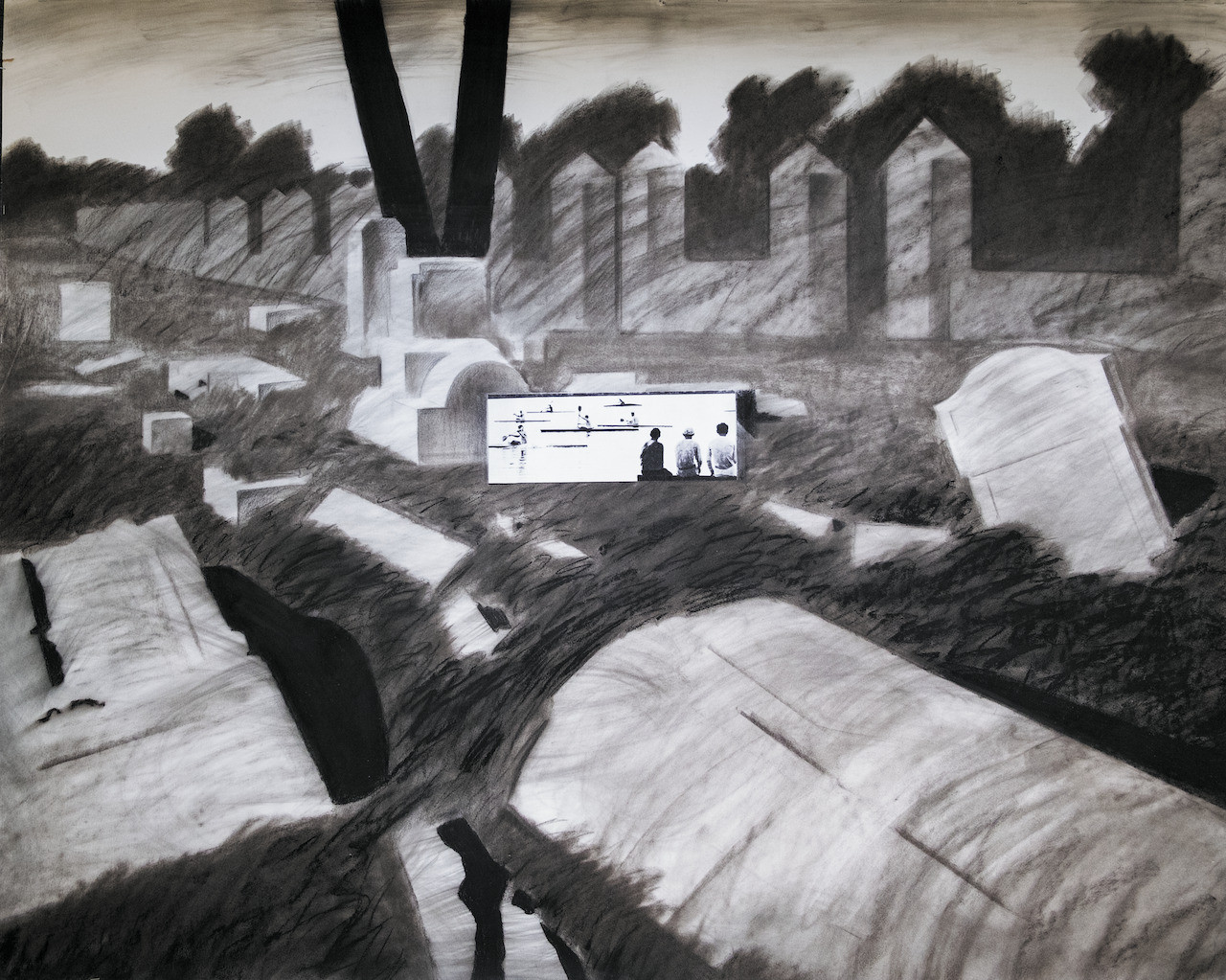

Nikita Kadan, Partially Hidden Landscapes, 2023, photograph and charcoal on paper. Courtesy the artist.

Nikita Kadan, Partially Hidden Landscapes, 2023, photograph and charcoal on paper. Courtesy the artist.

On October 12, 1941, between 6.000 to 12.000 Jewish persons were killed in occupied Stanyslaviv within one day by Nazi executioners and Ukrainian policemen — a massacre orchestrated by SS-Hauptsturmführer Hans Krüger that would come to be known as “Bloody Sunday” or “Blutsonntag” of Stanyslaviv. A mass grave was dug out on the territory of the New Jewish Cemetery to inter the victims’ bodies. The exhibition features a written report from 1966 by Julius Feuermann, who survived the Stanyslaviv Ghetto and the ensuing mass killing. He retells how the shooting stretched for the whole day and was carried out cooperatively by German and Ukrainian police forces. In an attempt to conceal the crime, three years later, prisoners from a nearby concentration camp were brought to the site to unearth the mass grave and destroy most remaining evidence. After the war, only nine people were convicted for their involvement in “Bloody Sunday”, and, according to various estimates, 40.000 to 120.000 residents with Jewish roots living in the Stanyslaviv region were killed during the German occupation.

The New Jewish Cemetery was closed and demolished in 1967 under Soviet rule and urban legends surround its exact location to this day. Mainly, it is widely believed that the cemetery was flooded and is now partially located under the municipal lake of Ivano-Frankivsk, the city’s largest artificial body of water. In her text for the exhibition, historian Maryna Siedova dismantles this myth and refers to historical maps that place the cemetery at a considerable distance from the lake. Contrary to the popular narrative, Siedova notes that the presence of old tombstones scattered around the lake can be attributed to a strategy originally initiated by the Nazis. For this, tombstones were removed from Jewish cemeteries and repurposed for other uses to expunge Jewish history from the occupied territories' cityscapes — a practice continued by Soviet authorities.

Returning to the artworks in the exhibition, Nikita Kadan’s series Partially Hidden Landscapes (2023) consists of large-scale charcoal drawings showing various anonymous landscapes with an emphasis on spatial expansiveness. A field with scattered tombstones resembling an abandoned cemetery is boarded by a wall that runs into the distance, while a photograph montaged onto the center of the drawing shows three people watching canoeists on a stretch of water, feeding into the myth of the cemetery submerged in the lake. Another less explicit drawing shows mere abstractions of headstones swallowed by a field, while the image in its center bears a direct connection to the city’s Old Jewish Cemetery, another burial place in Ivano-Frankivsk demolished under Soviet rule in 1957. In its stead, the “Kosmos” film theater was built shortly after and still stands to this day, albeit bearing little resemblance to the original modernist Soviet architecture. The relationship between the photograph and drawing in the last two works is left open to speculation, showing the modernist building of the regional administration of Ivano-Frankivsk montaged onto a drawing of a forest, and a flooded restaurant overlaid onto a drawing of a vast field.

The series uncovers the histories hidden within the landscapes which writer Martin Pollack considers to be “tainted” by the atrocities of 20th-century Europe [1]. In his writings, nature, usually connotated with notions of serenity, becomes a cemetery poisoned with bodies scattered away in anonymous graves in forests, fields, and meadows. Most of them were Jewish, Roma, anti-communists, and partisans — victims whose lives were extinguished and whose bodies were surreptitiously interred, denying them a proper burial. The absence of any trace of their identities underscores the deliberate erasure of these individuals, destined to be forgotten for eternity, with no one left to remember them.

“And why not?” writes Taras Prokhasko in his text for the exhibition, when he describes how from the 1950s onward residents of Ivano-Frankivsk were coming to terms with the dark history of the lands enveloping them instead of seeking out new commemorative forms. A sense of indifference and resignation took root, in resistance to the burdens inherited from recent history. Those who survived were no longer surprised by the erasure of their history, while the complicit chose to remain in silence instead of taking responsibility. In this shift, a kind of pragmatism emerged, creating space for the living and not the dead. The lake transformed into a venue for civilized leisure, with little concern for whether the cemetery lingered beneath its surface or not. As Prokhasko notes, even those apprehensive about alleged skin diseases from the water would enter the lake for a swim eventually.

The trickling water noises from the video work Flooding (2023), created in collaboration with filmmakers Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk, can be heard throughout the entire exhibition space. In close-ups above and beneath its surface, the camera inspects the contours of the municipal lake. Its lens moves slowly through the cloudy water, tinged green from the algae formations that blanket everything that settles on the lakebed. Poet Yuriy Izdryk reads a text in Ukrainian by psychoanalyst Harri Kraievets, weaving connections between the cemetery's flooding and the biblical Flood while underscoring the absence of an ark for the victims of the Shoah. In the aftermath of collective oblivion and lack of tangible remains, Kraievets characterizes the Jewish experience of the Holocaust as a state of psychosis. This metaphorical description suggests a psychological state marked by a profound disconnection from reality, a condition where the boundaries between memory, perception, and the tangible world become blurred. In the context of the Holocaust, this state of psychosis reflects the profound impact of trauma on the collective psyche, where the horrors endured defy conventional understanding and elude rational processing. Therefore, “Bloody Sunday” transforms into a vacant symbol, devoid of reference to reality beyond the symbolic realm. The sole reminder of the calamity manifests in the form of the lake, serving as the only authentic repository preserving the memory of the disaster that took place someplace else.

Nikita Kadan and Yurii Bakai, לובמ (Flooding), 2023, digital print. Courtesy the artist.

Nikita Kadan, Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk, film stills from video work Flooding, 2023. Courtesy the artist.

For a society deprived of part of its memory, the landscape remains the most reliable witness, but personal memories, urban legends, and artistic practices can all work as alternative forms of remembrance, resilient against dominant narratives. With Kadan’s The Inhabitants of Colosseum (2018), an attempt at an intangible commemorative form was included in the exhibition. Notably, this is the only piece not originally created for Flooding as it is centered around the guesthouse “Colosseum” in Regensburg, Germany. From 1945, it functioned as a satellite of the concentration camp Flossenbürg with over 600 persons, mostly Jewish, held captive. The facility was guarded by Ukrainian auxiliary police forces and during the day, they forced captives to move to a different part of the city for forced labor. According to eyewitness accounts, the daily commute of the prisoners wearing wooden shoes resonated against the stone ground widely. For a participatory performance, Kadan invited people to silently follow the path. Participants were provided wooden shoes, and the echo of their footsteps was preserved in a recording, which can be heard in a niche of the gallery space in Frankfurt.

Amidst the ongoing full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia, which is nearing its two-year mark, and the continuous attempts to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty, questions concerning a Ukrainian collective memory are raised with renewed urgency. Russian efforts to conceal their war crimes on occupied territories involve the removal of signs of destruction with disregard for the bodies left amid debris or hidden in mass graves. While entire cities lie in ruins, devoid of any remaining traces, the dead are once more placed at risk of fading into obscurity. Yet, in her curatorial introduction, Karavai asserts that the exhibition project is as much about collective remembrance as it is about collective forgetting, posing the question of whether the latter is conditioned helplessness or a convenient strategy. “Flooding” not only addresses Ukrainian complicity during the Holocaust but also exemplifies that any claim to a collective memory necessitates accepting responsibility.

Exiting 91 Galerie back into the busy street crammed with shops and cafes in Frankfurt’s city center, it becomes clear that for a society to cultivate an intentional and sincere practice of remembrance, active and collective labor is imperative; otherwise it will remain susceptible to descending into empty rhetoric.

[1] Pollack, Martin: Tainted Landscapes, Residenz Verlag, 2014.

Exhibition view Flooding. 91 Galerie, Frankfurt am Main. 2023. Photo: 91 Galerie.

Exhibition view Flooding. 91 Galerie, Frankfurt am Main. 2023. Photo: 91 Galerie.

Flooding

07/12/2023 – 31/01/2024

With works by: Nikita Kadan, Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk, Harri Kraievets (Neue Jüdische Kunst)

Curators: Alona Karavai, Anton Usanov

Production: Marta Savitska

91 Galerie

Schillerstraße 16

60313 Frankfurt am Main

91 Galerie is a Frankfurt-based non-profit contemporary art initiative of Perspektive Ukraine e.V.