Kunstverein München

by Sarah Messerschmidt

Notes on the performance series held in the Hofgarten between May and September 2023

with performers Magdalena Mitterhofer and Shade Théret, Luisa Fernanda Alfonso, Jan Kunkel, Vera Karlsson and Alie O., and an epilogue by Shola von Reinhold

how leisure always imitates labor, Jan Kunkel, Alie O. and Vera Karlsson, Hofgarten, 9 September 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

Munich’s Hofgarten is fairly haunting. It might well harbour a few phantoms, but what I mean is that it is evocative, stirring. It was designed that way. The park is the quintessence of a Baroque Paradise landscape established for a Bavarian Duke whose imperative, like that of any other European royalty of the age, was to demonstrate his princely virtue through magnificence. It was—and is—a deliberate ground for fantasy.

Despite being a public area for many years now, the park remains cloistered from the surrounding city. The idea of ‘public’ is complicated by its blueprint; its architecture is intended to partition. For some, there is solace in the calm that is naturally afforded by an enclosure of walls. For others, the seclusion retains an ambience of social regulation, of soft surveillance and monitoring.

I haven’t settled on how it makes me feel, but I must admit I like to pretend when I am there. The place makes an excellent scene for projection. Strange how one can be hypnotised by details: the bells start pealing the hour and I am suddenly three centuries in the past standing on a lawn made for hermits. I was at least told that so-called ‘ornamental people’ lived in its copses once, and it is towards them that I feel most curious. It’s tempting to wonder openly at the discreet and hidden lives of the garden, at what’s off the record more than what’s on it.

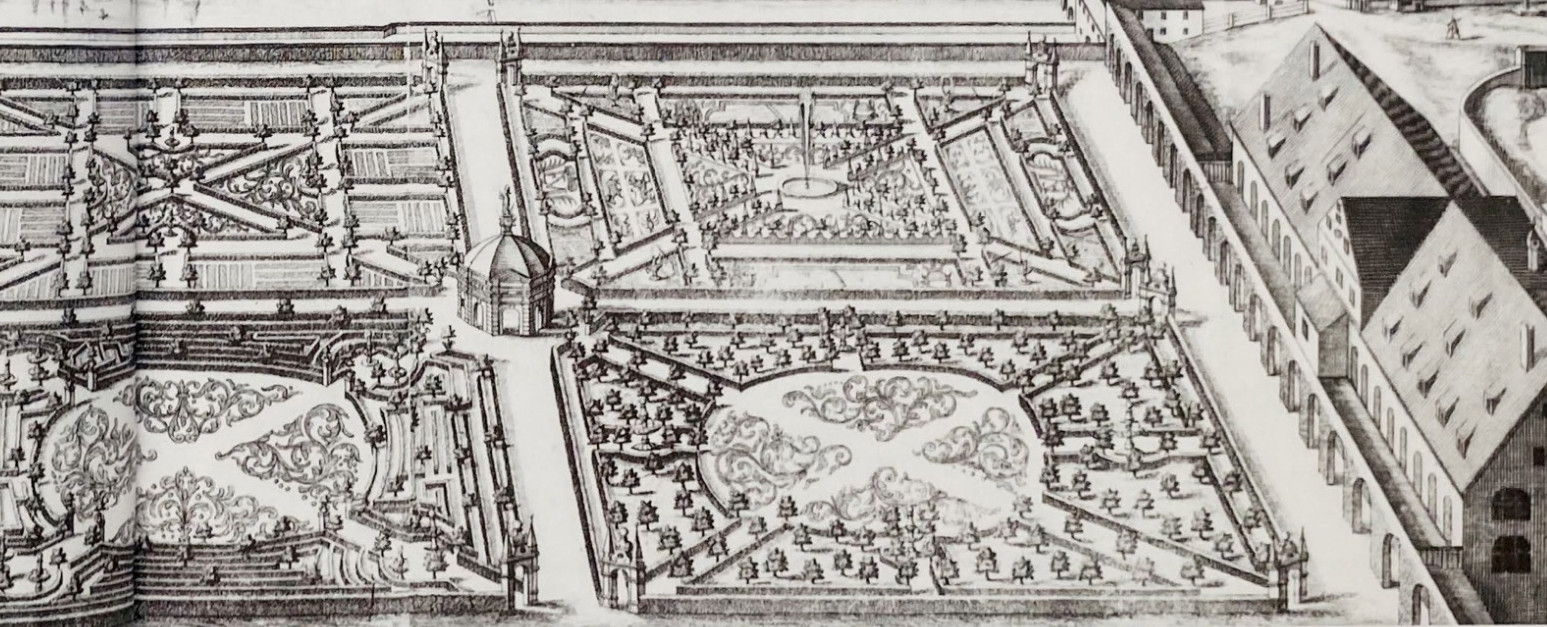

Detail: Michael Wening, copperplate engraving of Hofgarten in Munich, 1701

Gina Merz wonders openly too. Assistant curator at the Kunstverein Muenchen, which has been lodged for two hundred years in an arcade along the perimeter of the garden, she was interested in releasing her work from the snare of official accounts of history, choosing instead to animate narratives that have had no comfortable place in Kunstverein’s formal records. In a series of outdoor performances titled ‘Park,’ Merz undertook to critically engage with the Kunstverein’s institutional legacy through the Hofgarten, deconstructing and complicating the more orthodox versions of its history by opening it to storytelling and nuance. To do so specifically through performance is to recognise the histrionics involved in history-writing. I find Amelia Jones helpful, when she writes about the “potential of performance to put pressure on how we write history” and to “…thwart structures of [aesthetic] judgement.” [1] Everything, even the most standard of archives, contains some kind of theatre, and in the park we have a permanent stage.

The Hofgarten is an imaginative site. For one thing, it was an attempt to manifest the stories wealthy landowners told themselves of an honest pastoral asceticism with traces of Druid lore—a romantic 18th century vision of nature free from the unpredictable tangle of reality. Such a script in fact plays time and again, as I later realised, from Marie Antoinette’s fantasy hamlet to the Kardashian miniature village. For another, it’s the site of buried, undisclosed, and partly invented stories in wont of a rightful awakening.

~~~

Erster Teil / 1st Sequence

rude no. 1, by Magdalena Mitterhofer and Shade Théret

For this first act, a personality is summoned. 19th century dancer, thespian and notorious misfit, stage name Lola Montez. Personified by Mitterhofer and Théret, she and her double walk in lockstep down a long corridor. Wayward. Prowling. Montez was judged to be too tawdry by the bourgeois intellectual circle that congregated at the Kunstverein in her time, and this, says the duo, is a point to stick on. One look around the swanky estate is enough to understand that there are two sets of rules, one for those who make them, and another for those they are meant to bridle. She was evidently a disarming character: among other worldly intrigues, there was a dalliance with Franz List, a friendship with George Sand, a controversial double role as both countess and courtesan. It should be noted that Montez was eventually admitted as a member of the Kunstverein at the request of King Ludwig I, most probably because she was his mistress.

rude no. 1, Shade Therét and Magdalena Mitterhofer, Hofgartenarkaden, 20 May 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

Embodying Lola’s charm, the 21st century apparitions wear rhinestoned denim and noughts-era heels, parading around in a kitsch sartorial code to show an affinity with the frivolous maverick

the femme fatale

the reckless vamp.

Ben Cruchley, a concert pianist, sits to the side at a baby grand on wheels. He is their show-tune maestro, tinkling out melodies and the occasional airy sonata. For each small chapter of the performance, the three performers trundle the piano several paces down the arcade in front of the Kunstverein with an audience following not far behind.

I once glued myself to a vitrine with a mixture of super glue and mashed potatoes.

A shopping bag swings full tilt around the axis of a shoulder joint, it’s holding water. Will it burst? We are made to think of an exploded aquarium in Berlin, anthropic hubris, all those fish destroyed (the grim fate of creature containment). [2]

I’m a sing-song, a thingamajig, a tiktok, a plastic bag in the wind.

While one sits in a doorway smoking, the other engages in a kind of constant flow, a liquid ballet. She raises a tall shoe to the level of her eyes—deadpan, decadently serious—executes a nimble détourné in impossible footwear. The first interjects: ‘I have nothing to confess to you… I will dance my own dance!’ through exhaled cigarette smoke. The two are unshakable, inscrutable oddballs, enfants terribles, who recite their monologue in tandem, playing variations on a character.

rude no. 1, Shade Therét and Magdalena Mitterhofer, Hofgartenarkaden, 20 May 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

Without breaking their discourse they construct a makeshift shelter from a white cloth and bits of wood, and climb inside. It’s the apex of their twinly complicity, standing on their knees inside an odd little nest. There are more recitations –

I will speak of your eyes

although they are closed.

Tell me, where is each stubborn-colored iris?

Where are the quick pupils that make

the floor tilt under me?

I see only the lids, as tough as riding boots.

Why have your eyes gone into their own room?

Goodnight they are saying from their little leathery doors.

– and a short burst of melodrama in mimed fellatio.

Later, the piano is wheeled another several feet along the corridor, and the group assumes position for a final number. I catch a small smirk. A wry jingle <<ich bin die fesche Lola, der liebling der Saison>> sung in gravelly burlesque caricature.

Masterpiece, Luisa Fernanda Alfonso, Dianatempel, 30 June 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

Zweiter Teil / 2nd Sequence

Masterpiece, by Luisa Fernanda Alfonso

In the geometric centre of the park stands a domed pavilion to exalt Diana, goddess of the hunt and of the rural. She is a deity who is also celebrated in neopagan rituals, which is curious, and I wonder at this appetite for pagan religion in the neighbourhood of at least five historic churches. The nostalgia recalls Silvia Federici, who said this about witchcraft: “The revival of [pagan] beliefs is only possible today because it no longer represents a social threat… does not jeopardise the regularity of social behaviour.” [3] There’s no doubt that in its beginning, the garden could sustain the pretence of a rustic utopia, one made for solemn contemplation and peopled by quaint ascetics, in the knowledge that a different normative order continued unimpeded beyond its walls.

~~~

Horns begin to sound as the hour gives way to dusk. A summons to the temple. Luisa Fernanda Alfonso stands on a stack of subwoofers in the centre of the pavilion and begins in a throaty moan-singing, deep and sonorous. The silhouette of an audience surrounds her on all sides. She sings a medley of popular Latin American songs pitched down, exaggerating an atonal voice (120bpm slowed to 30bpm) to capture distorted and faltering waves in the sustained notes. Her collaborator, composer Peter Rubel is off to one side electronically manipulating this sonic evolution.

Masterpiece, Luisa Fernanda Alfonso, Dianatempel, 30 June 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and and STUDIO CNP

She waves her dainty, ruffled arms and pulls a tragic face. This is a character dance, a blend of Cumbia and Mariachi drama. While what is danced is by many measures typical of each tradition, the dancer distorts the conventionally gendered archetypes found in Columbian and Mexican folk styles, particularly the virile, turning herself into a hybrid figure who performs all parts in what are usually partnered roles. When she sings, her voice is wavering and deep. Under her full skirts she wears the clinging breeches of male performers, designed to enhance bravado. When she moves, she commingles feminine and masculine emotive force into a swaggering, passionate softness.

To the side, a group of salsa dancers linger under an archway. They have just finished a session of their own, and now watch with interest as Alfonso’s hands draw wide arcs in the air, cascading white ruffles down her arms. Performances in public space are so enriched by this kind of serendipitous fluke.

A choir of standing loudspeakers wearing frilly gowns faces her, chanting the singing back in delays. In chorus the voices sound uncanny and a little robotic. But the low speed enhances the emotional charge of the original songs, usually so much brighter, and Alfonso is up there in lament with her speaker-sisters.

The sound bounces on stone. The dome makes for a reverberating, supple environment. Gradually, however, the choir begins to fall apart. It loses coherence, goes out of tune into a caterwaul of disharmonious voices. The congregation melts in time with the oncoming twilight.

how leisure always imitates labor, Jan Kunkel, Alie O. and Vera Karlsson, Hofgarten, 9 September 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

Letzter Teil / 3rd Sequence

how leisure always imitates labor, by Jan Kunkel, Vera Karlsson and Alie O.

Wedded couples perform constantly in the Hofgarten. I’ve witnessed plenty there staging photoshoots. One such pairing felt moved to co-opt, for just a few minutes, Cruchley’s piano in rude no. 1, which was rather amusing, and we have to admit that intervening in public space with performance leaves a healthy margin for counter-intervention. Jan Kunkel, in communion with two collaborators Alie O. and Vera Karlsson, enacts this ritual of the marriage bond, not simply for its performative traits, but also for what the demonstration of marriage can expose about possessive love and systems of domination.

Unlike in the previous pieces, the area of this performance is totally dispersed. Three spooky brides, marriage spectres, rove around like Dickens’ ghosts of Christmas. They are shrouded, hiding in bushes, ambling fawn-legged over stone steps and neat shrubbery. They roll around in the grass, they scale buttressed ‘pleasure-houses,’ they drift forlornly trailing ribbons of tulle behind them. Somebody cuts into a cake.

how leisure always imitates labor, Jan Kunkel, Alie O. and Vera Karlsson, Hofgarten, 9 September 2023. Image courtesy of Kunstverein München, Lara Fritz, and STUDIO CNP

‘The name of the husband is one of the strongest insignia of patriarchal power,’ writes Jacqueline Rose. [4] For Kunkel, the Hofgarten is a symbol of bloodlust and of the strive for political dominance summed up in opulent violence. What is described by Walter Benjamin in “The Origin of the German Tragic Drama” applies here: the Trauerspiel is and was a genre that substituted history for myth, which in effect naturalised the “sovereign violence” of 17th century colonial endeavour—the same forces that produced such a decadent, verdant park, and which endorse lavish wedding displays. [5] The trio dissect the garden’s political theatre. They work with spatial memory to construct an inverted image of matrimony.

In marriage, partners become familiarised as othered subjects. One becomes possessed, possesses the other. The folding of subjects into one another is expressed materially through the layering of garments and cloth that adorn the players. Their work is informed by everyday paradigms of performance, merging the quotidian and the patriarchal frameworks that oversee institutional coupling as a natural part of human life.

The piece is scored by strange, atmospheric music that blends with more spontaneous environmental sounds—children shouting, the noise of animals, chatter—and the padded footsteps of unshod feet (Kunkel wears pretty lace stockings; one big toe pokes through a hole in the netting). Performance is a balance between imitation and substitution, and in this performance an equilibrium is achieved through the subtle exercise of each, and an attempt at integration into the surrounding activity of public space. The thrust here is that transgression is so embedded in performance history that the piece instead seeks out motifs that have been assimilated into regular culture, so that the limit between what is lived and what is performed is blurred. Through this choreography, the three performers also seek to capture the accepted myths of nuptials that stabilise the bond between institution and infrastructure to reveal how power is reified in a bucolic idyll.

Detail: Prince Luitpold with company at the arcades in the Hofgarten, 1905

[1] Amelia Jones, ‘Unpredictable Temporalities: The Body and Performance in (Art) History’, in Performing Archives/Archives of Performance, eds. Gunhild Borggreen and Rune Gade, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2013, pp. 53/54.

[2] The performance makes oblique reference to the AquaDom disaster in Berlin in December 2022 that unleashed a deluge of over 1 million litres of water and caused the death of 1500 tropical fish. which this author interprets as a contemporary analogy to the consequences of unwieldy Renaissance decadence. https://www.euronews.com/2022/12/16/wave-of-devastation-as-huge-aquarium-explodes-in-berlin

[3] Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

[4] Jacqueline Rose, The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, London: Virago, 1991.

[5] Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, New York: Verso Radical Thinkers, 2009.

Park

Performance series in the Hofgarten

with Magdalena Mitterhofer and Shade Théret, Luisa Fernanda Alfonso, Jan Kunkel, and an epilogue by Shola von Reinhold

20/05, 30/06, and 09/09/2023

Curated by Gina Merz

Kunstverein München

Galeriestr. 4

(Am Hofgarten)

80539 Munich